Before L.M. Montgomery married, she had serious shopping to undertake, choosing fabrics, styles, and embellishments for her Edwardian wedding trousseau, including a stunning silk gown adorned with crystal beadwork. Montgomery’s elaborate wedding plans indicated her new wealth, her growing self-confidence in her place in literary society, and an indulgence in fashions she loved.

As well as being the modest house where the author’s life began, the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace in New London, Prince Edward Island, is the proud holder of her wedding attire. Each morning after the doors are unlocked and the parlour curtains undrawn, a silk replica of Montgomery’s Edwardian dress shimmers. The subtle light enhances the embroidery of her original veil and the two slim, heeled slippers of velvet-lined, ivory satin that once hugged her small feet. Beside them reside Montgomery’s velvet, black-beaded shoes, which were worn at elegant dinners on board the Megantic and Adriatic, the two ships the Macdonalds took to and from the United Kingdom on their honeymoon.

But before they embarked on that memorable three-month honeymoon, Montgomery had purchases to make.

The Trousseau

On May 8 I went to town to attend to shopping and dressmaking.

—Montgomery, CJ 2 (7 May 1911): 4011

After wearing black to mourn the passing of her maternal grandmother on 10 March 1911, Montgomery quickly left the dreariness of the shade and winter fabrics behind to be married in early summer. During the Edwardian period, women might mourn a parent for one year, and a grandparent for six months (William L. Clements Library). Lucy Macneill was both mother and grandmother to Montgomery, but Montgomery's mourning period for her ended at approximately three and a half months, taking into account what may have been a week or two before Montgomery was able to obtain suitable black clothing, possibly from a local seamstress. Mary Rubio compares Montgomery’s “sombre encasement” of dark coat and hat in a photo taken on the shore that Montgomery entitled “A dream fulfilled” in her journal (CJ 2 [24 May 1911]: 408) with her previous “diaphanous wrap” image of 1903 that was photographed at a sea cave by her friend Nora Lefurgey, saying she looked “as formidable as a nun in black habit” (Lucy Maud 151). However, the “dream fulfilled” portrait is of Montgomery in mourning, when the twilight air at the New London shore could be cool. She was not mourning her marriage-to-be, as I believe Rubio suggests, but the loss of her grandmother and former home in Cavendish. Montgomery felt a “pang” when she drove away, with one last glimpse of her “distant homeland shore,” although her “long dream had come true and brought to me all I had dreamed into it”—the excitement of a wedding, an ideal honeymoon, and then a stable home with a kind man (CJ 2 [24 May 1911]: 408). Following her deep respect for tradition, in the “dream fulfilled” photograph Montgomery was still wrapped in black.

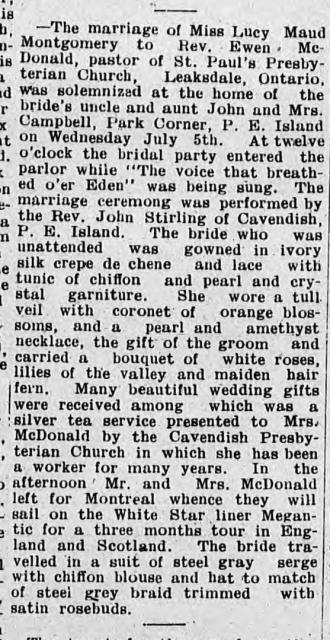

There were fewer than four months between the death of Montgomery’s grandmother Lucy Macneill and her upcoming marriage to Ewan Macdonald. As Rubio says, the engagement, which came about in October 1906, may not have been such a secret after all (Lucy Maud 124, 131), because the announcement of her betrothal to family and friends after the sudden shock of Grandmother Macneill’s death should have seemed like the leap of a woman who was making a rash decision in her grief. Yet there is no corresponding discussion in her journals of the utter surprise her dearest and closest may have felt. Since Montgomery must have had Macdonald as a caller when her grandmother was alive, and they exchanged letters and gifts, particularly at Christmas but possibly for other occasions such as Valentine’s Day and their birthdays, it seems as if the engagement may not have been a revelation to those in her immediate circle. Her dear friend and cousin Frede Campbell wrote to Montgomery in her ten-year letter dated 24 March 1907, “Why do you wear that diamond only at night and when there is nobody near to admire it? Dear Mrs. Macdonald, do you remember your courtship and how sly it was all done?” (SJ 5 [5 Apr. 1937]: 155). Montgomery notes in her journal entry of 28 January 1912 that the night before she left Cavendish to live with her aunt and uncle in Park Corner, the “Cavendish people gave me a farewell reception … and presented me with an address and a silver tea-service” (CJ 2: 377). The silver service was later described in the 8 July 1911 wedding announcement in The Charlottetown Guardian as a wedding present from Cavendish Presbyterian Church (7), although the 22 March article describing the evening at the Stirling manse said she was given a “purse” (2), filled with money, we can assume.

Montgomery’s husband-to-be, Ewan Macdonald, was a minister with a rural two-point Presbyterian charge in Leaskdale, Ontario. This career did not provide the substantial income required to pay for the extravagant wedding and honeymoon his fiancée envisioned. Montgomery’s parents were both deceased, as were her grandparents, and none of them left her a significant legacy in cash or property. But Montgomery had published four novels by the time of her wedding, with Anne of Green Gables being a runaway hit. Rubio notes that in February 1910 Montgomery’s royalty cheque from L.C. Page, her Boston publisher, was $7,000, about half of what the prime minister of Canada earned the same year (Lucy Maud 130). Montgomery was a woman with money in her purse, and now that she was free from caregiving, the author was ready to splurge on herself.

In 1910, Montgomery began—although she did not know it at the time—a pre-wedding clothing spree, indulging in beautiful clothing and accessories that she admired. “Whatever worries life may still hold for me ... it does not seem likely that lack of money will hereafter be among them” (CJ 2 [29 Nov. 1910]: 319). First, she purchased brown silk and the necessary trimmings for a dress to meet Governor General Earl Grey and others at an informal gathering in Orwell at Dr. Andrew Macphail’s home (CJ 2 [7 Sept. 1910]: 304). Shortly afterward, Montgomery shopped in Charlottetown for “a fine set of mink furs” because she had arranged to meet with her publisher, Lewis Coues Page, in Boston, Massachusetts. When she visited Page and was celebrated by his publishing firm and family, Montgomery revealed in a journal entry for 29 November 1910 how much she loved fancy clothing, entertainment, and fine dining: “I like dinner in the evening. I like the soft lights gleaming on pretty faces and white necks and jewels and beautiful gowns. And I must candidly say that I liked the life of the Page menage and that it fitted me like a glove” (CJ 2: 317, 325–26).

While in Boston, Montgomery made further purchases: “a brown broadcloth suit” and an “exquisite afternoon dress of old rose cloth, hand embroidered in pink silk,” which cost eighty dollars. She said, “eighty dollars means no more to me now than eight once did. There have been very few years in my life when eighty dollars would not have covered the cost of all the clothes I got in that year.” As well, she obtained “several pretty things, including a sweet little hat of black velvet with a pale pink rose at the side” and “a sweet little dress of apricot chiffon over silk, with all the appurtenances” (CJ 2 [29 Nov. 1910]: 324, 326, 328). On 13 December 1920, Montgomery admitted to being “very fond of pretty dresses, hats and jewels” because she could not enjoy herself if she was not well dressed: “I don’t like to be in any company where anyone is better dressed. I do not feel happy when I am alone if I am not prettily dressed. I am especially fond of lace, pearls and diamonds.” As well, she liked “the admiration of men” and “luxury and leisure” (CJ 4: 287, 289).

After her grandmother died in the winter of 1911, Montgomery moved in with her Campbell relatives in their Park Corner farmhouse until she married. As she writes in her journal on 8 June 1911, preparations for the wedding, repast, and honeymoon kept her and her two cousins, Frede and Stella, “intensely busy.” In particular, a flurry of fittings for clothing was done locally, while other items were ordered out of province or out of country. “My trousseau, which I had made mainly in Toronto and Montreal, began to arrive ... My things were pretty. I had worn black for grandmother all the spring but I laid it aside when I was married” (CJ 2: 413).

One of Montgomery’s trousseau photos hangs on the Birthplace wall beside the dress case. It is a slightly out-of-frame image, taken on the lawn using what appears to be a lilac bush and other trees as background, by a photographer who may have been slightly less experienced than Montgomery. “These are snaps the girls took of some of my dresses,” she notes in a retrospective entry dated 8 June 1911, speaking of her cousins Frede and Stella (CJ 2: 413). Montgomery could have set up the shots in her Aunt Annie’s parlour, but the exterior natural light was flattering and easier to use as it fell almost directly on her new attire, despite the encroachment of laundry on the line behind her in some of the photos. Although several dresses, a suit, and a wrap were photographed, many articles of clothing were not, including those mentioned in the 8 June 1911 journal entry: “a linen dress, a pink muslin, one of white embroidery, and several odd waists.”2 As she was quickly moving from mourning black into lighter wedding colours, her going-away attire was a “suit of steel gray cloth, with gray chiffon blouse and gray hat trimmed with a wreath of tiny rosebuds. My long wrap was of gray broadcloth” (CJ 2: 413). Steel grey was a modest, practical, neutral tone, a step away from black and excellent for potentially dusty travelling as well.

Montgomery probably visited a dressmaker’s shop in Charlottetown, where she examined books of fashions, and the resulting orders would be sent to seamstresses to create the trousseau with a rapid turnaround, whether on-island or off. Although Montgomery purchased many special items after her initial literary successes, no shopping spree was as lavish as her trousseau preparations. Dresses, wraps, and hats were discussed in her journals, but there would also have been dainty underclothes, nightwear, gloves, and jewellery to round out her purchases—and perhaps leather suitcases and trunks to carry everything.

Chesley Clark of Rusticoville related in 1986 that his mother had mentioned the author’s dress fittings at their house. An early sewing machine was used for Montgomery’s original wedding gown fitted and sewn by Margaret Bulman (née Stewart) of Cavendish. Bulman was Clark’s step-grandmother and a local seamstress favoured by Montgomery. An unsigned handwritten note in the Confederation Centre wedding-dress files, which obtained information from Clark, states that Bulman sewed Montgomery’s wedding dress (“Information”). Clark's mother was seventeen years old in 1911 when Montgomery visited his step-grandmother’s house for fittings, and in 1986 when the note was written, Clark still owned the sewing machine used to create the dress.3 In a journal entry dated 6 February 1923, Montgomery recalls “Maggie Stuart [sic], a Cavendish dressmaker who never had any training but was a born artist in her line. I’ve never seen her dresses equalled anywhere; … her ability to make ‘a perfect fit’ was something uncanny. Her dresses always made you, in the country phrase, look as if you had been melted and poured into them” (CJ 5: 115).

In a 1975 newspaper interview conducted by Heather Moore for Prince Edward Island’s Eastern Graphic, Addie MacCannell, then ninety-four years old, remembered that she worked on Montgomery’s wedding dress and trousseau wardrobe. The sewing was done in Charlottetown’s old Hillsborough Square under the direction of Mrs. Charlie Patterson, who had a dressmaking shop there. “Miss Montgomery’s clothes were nice,” she recalled. “They were made of good quality cloth but they were plain, nice and simple.” It seems likely that MacCannell worked on Montgomery’s trousseau dresses but not the wedding gown, given Clark’s information points to Bulman sewing the gown, the family memory of Montgomery visiting the house for fittings, and Montgomery’s own preference for the dressmaker. As well, MacCannell noted that Montgomery’s clothes were “plain”—which the elaborate wedding gown was not, particularly with its fine lace, silk from Paris, and crystal beading—and that it had “puffed sleeves” (Moore), which she may have misremembered from reading Anne of Green Gables.

The preparation of her special trousseau would have taken every one of the weeks of the spring and early summer before the wedding on 5 July 1911. Coordination with her fiancé would be paramount, particularly for honeymoon details over a lengthy trip to the United Kingdom and preliminary household requirements for their move into the manse in Leaskdale, Ontario. But the most important item for Montgomery was designing her wedding gown, and this she probably undertook herself, and which required frequent trips to Charlottetown and Cavendish for fittings.

In the decade before the Montgomery-Macdonald wedding, Edwardian clothing had taken a turn away from much of the heaviness of styles when many women had emulated fashions worn by Queen Victoria to simplicity with lighter, flowing fabrics (Woods). The Edwardian era right up to the beginning of the Great War in 1914 was believed to garner much of its fashion sense from the difference between Edward and his mother, Victoria. While the Victorian era is remembered for its fashion extravagance—like the puffed sleeves in Anne of Green Gables—the Edwardian era gave way to less complicated structure (Reddy). “My wedding dress was of white-silk crepe de soie with tunic of chiffon and pearl bead trimming—and of course the tulle veil and orange blossom wreath,” Montgomery relates in her journal on 8 June 1911 (CJ 2: 413).4 The chiffon tunic was a short, blousy jacket, embellished with pearl beadwork on the bodice and above the elbows. Crepe silk is a lightweight, sumptuous fabric with smooth finish that draped well, suitable for items such as wedding gowns. As seen from the side, Montgomery’s Edwardian gown was, as cultural historian Hannah Rose Woods describes, a typical S-shape with a “pigeon” chest and puffy skirt back: “the new Edwardian silhouette was that of the S curve—a shape that pushed the hips back and the bust forward, exaggerated by floppy blouses that hung over the waist at the front.” Woods further notes that the “ideal feminine figure of the period” was “a mature, womanly silhouette with a pigeon-shaped monobosom.” At age thirty-six, Montgomery carried off that look.

One Islander who provided reminiscences in Lucy Maud Montgomery Remembered says that Montgomery’s wedding dress was sewn “from fabric that Lucy Maud had ordered from Paris” (Johnstone 32). It could be assumed that if the wedding dress fabric was from Paris, France, then it may have come to her seamstress by way of a supplier in Toronto or Montreal. Despite the wedding being a small affair in the parlour for select friends and family, Montgomery was extremely proud of her new wardrobe and happily displayed her garments to interested parties. For instance, when a Long River choir practice was held at the Campbell house before the wedding, Montgomery, who had been invited out for the evening, asked Ella Campbell, her cousin George’s wife, to lay out her wedding dress and veil on a bed for members of the choir to see (Johnstone 31–32).

According to Sheri McBride from the Department of Family and Nutritional Sciences, University of Prince Edward Island, the tulle veil had a coronet of wire and wax orange blossoms trailing about ten inches down the sides (Documentation 14). Orange blossoms traditionally signify purity and love, especially in the Christian faith as with Queen Victoria when she married Prince Albert. Rather than a tiara, Victoria chose a wreath of orange blossoms to signify chastity (Royal Household), and pale silk and orange blossoms became Montgomery’s choice as well. The tulle was slightly heavier than the netting used on the gown and was cut in one irregular quadrilateral of approximately sixty-seven inches at the top, eighty-two inches at the bottom, and ninety-five inches in length. Some of the top was gathered to create a crown at the centre top, where the orange-blossom coronet held the tulle on Montgomery’s head (Documentation 14), but the veil would not have covered her face. The veil was embroidered in a simple, continuous loop stitch with ivory-coloured thread, probably silk.5

The Wedding

I wore my white dress and veil and Ewan’s present—a necklace of amethysts and

pearls. My bouquet was of white roses and lilies of the valley.

—Montgomery, CJ 2 (2 July 1911): 417

Since she was familiar with newspaper offices due to her short-term proofreading position in Halifax with the Daily Echo in 1901–1902, Montgomery may have submitted her own wedding announcement to The Charlottetown Guardian to be printed the day of the event, 5 July 1911. The first announcement said the wedding would take place that day at Park Corner, solemnized by Rev. John Stirling. Rev. Macdonald “is a native of Valleyfield in this province and a nephew of Capt. Alex. Cameron of the S.S. Empress ... At 4 o’clock the happy couple will leave for Summerside and will leave by the Empress on the following morning en route to England” (“The Marriage” 5).

Interestingly, the marriage announcement sat right beside an advertisement for Kodak cameras at the Johnson and Johnson store, on a day when Montgomery apparently did not have photos taken at—or did not save them from—her own celebration. Notwithstanding calls by Montgomery researchers and by an unsourced, undated newspaper article that requested the Island community seek old images of the author in her original gown, decades of searches have not revealed any wedding photographs of Maud and Ewan Macdonald as a newly married couple, nor of them in the company of their cherished wedding guests (Jorgensen).

If Montgomery did not have a reporter attend her wedding ceremony, she probably would have had photographs taken by family or friends. Her attention to detail—including the handwritten note kept with her trousseau slippers at the Birthplace and fabric swatches in her scrapbook of trousseau clothing—proves the wedding dress to be an important article from her personal history, particularly if it was hand-beaded and constructed of fine fabric imported from France. Had there been any imperfect photographs taken by an amateur photographer, such as Frede or Stella, Montgomery may have lamented the circumstance in her journal but nonetheless included the photos. After all, Frede and Stella had snapped images of her honeymoon attire, and Montgomery included the photos with her 8 June 1911 journal entry (CJ 2: 413). Montgomery may have lamented the circumstance in her journal but nonetheless included them. Many inferior photographs were saved in her personal items, despite imperfections such as blurred images or out-of-frame composition. And there could have been photos of Montgomery with different family members and friends as evidenced by how many she had taken of her trousseau wardrobe or, later in Leaskdale, of her children, husband, and cousins. Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston remark that Montgomery razored pages out of her journals and replaced them by hand (Introduction xx), and in a 1986 letter to Kevin Rice, then registrar of the Confederation Centre Art Gallery, Rubio suggests that the author did not keep photographs of her wedding day.6 For example, Montgomery included in a journal entry for 2 July 1911 exterior and interior images of the house and parlour in which she was married (CJ 2: 416), but no photo of the wedding guests in the room or of the celebration dinner afterward. It is possible that Montgomery destroyed all wedding images at a later date, although it would have been difficult to explain the loss to her husband and sons. Her camera was available again a few days later for honeymoon shots on board the ship Megantic with Ewan, when Montgomery took photos of the groom and other passengers on board, but the newlyweds did not set up any further photographs of the bride travelling in her trousseau outfits.

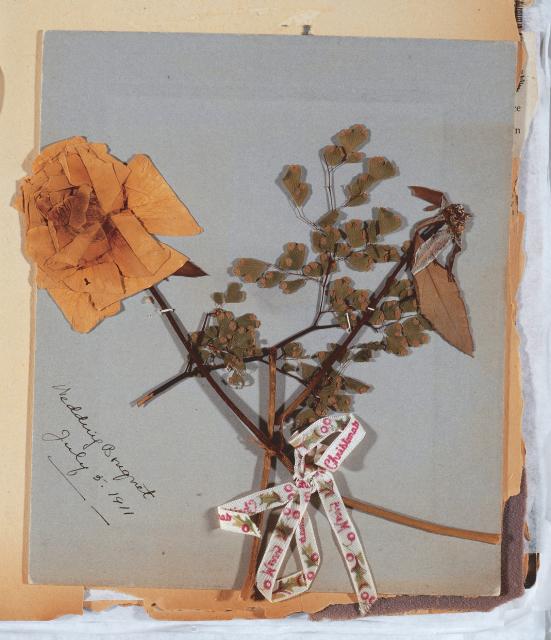

A second wedding announcement, printed on 8 July 1911 in The Charlottetown Guardian after they departed on their honeymoon, relayed more complete details on Montgomery’s gown, bouquet, and travelling suit, her gift of a silver tea service from Cavendish Presbyterian Church, and her honeymoon plans. The details may have been obtained from the bride, as the notice specifies the “ivory silk crepe de chene and lace with tunic of chiffon and pearl and crystal garniture” of her dress. The Guardian also noted that she descended the Campbell staircase unattended, carrying a bouquet of white roses, lilies of the valley, and maidenhair fern (“The Marriage” 7). A portion of her bouquet (two roses and a sprig of fern) was preserved in her red scrapbook.7 Even her bouquet—the white roses (which echoed the dress’s beaded roses and fabric rosette at the back of her waist), lilies of the valley, and maidenhair fern—must have been attained at some expense from a florist. Although white roses could have been cut from the Campbell gardens and maidenhair fern may have come from a plant that her Aunt Annie grew in the parlour, lily of the valley was out of season by early July and would have to be obtained from a florist.8

The Dress Through the Decades

In the decades since the wedding gown began being displayed at Montgomery’s New London Birthplace, textile historians and conservators have examined the object and offered lengthier accounts of Montgomery’s dress than her simple description on a journal page. A letter from Linda Berko, curator of collections and conservator with the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, to Kevin Rice in December 2000 described Montgomery’s wedding dress as having “loosely woven silk overlay on bodice and skirt with elbow length cap sleeves and ¾ length skirt.” Beaded banding, approximately one-and-a-quarter inches wide and handcrafted of iridescent glass pearl-shaped beads and small white seed beads, decorated the sleeves and skirt overlay. The repeated rosette and leaf motif9 was couched—a method of fastening the beads with small, regular stitches onto two layers of netting and hand-stitched to the gown’s oversleeves and overskirt (Documentation 4). Silver-coloured—or steel-cut, as Montgomery referred to them—beads adorned the edges of the band (Berko).

Although Montgomery stated twice in her journals that her gown was white, the Guardian newspaper article mentioned ivory. The colour of the gown and thousands of different beads could have aged from white; however, they currently appear to be ivory. The dress has a silk taffeta underskirt with two floor-length panels at the front and five longer ones around the back (Berko), which would have allowed the taffeta beneath to trail down the Campbell-house stairs with a soft rustling sound. Net lace was used for the high collar, yoke, and long inner sleeves, and lined with a fine voile (Berko). The outer sleeves appear to be kimono style, continuing the light silk overlay of the bodice, with no visible seams to suggest that they were cut separately. Research by McBride suggests that the full-length, set-in sleeve beneath was constructed of the same lace as the stand-up collar and chest insert (“Labels”). Extensive use of pearl bugles, seed pearls, glass lozenges, and other tiny glass beads surrounds the lower area of the yoke and finish at the top of the shoulders. Scalloped rows of beading (which vary in count) lead to three large and two small decorative bead medallions arranged from the shoulders to the front, ending in a large central medallion from which hang two beaded tassels. In her research recorded in Documentation of L.M. Montgomery’s Wedding Dress, McBride observes that each of the decorative medallions has central diamond-shaped beads of what appears to be iridescent glass. Many of the other beads, such as the pearl and bugle beads, also seem to be iridescent glass. The medallions are couched on the same small pieces of lace as used in the collar and sleeves, probably with a fine silk thread (3). The two tassels hanging from the centre medallion were crafted identically of white seed beads, two round iridescent pearl beads of different sizes, and long lozenges. Randomly placed solid white beads—usually seeds, but sometimes tubes—seem to be a mismatch with other cream-coloured, opalescent beads. The repeated motifs and sizes of the beadwork led McBride to believe the bodice appliqué was “intentional and planned,” although she also questions whether the tassels and roped chains may have been “added in the 20s” (Documentation 2). However, images of the era have shown that tassels were used circa 1910 (Oakes, “Real Wedding Dresses”).

The waist of Montgomery’s wedding dress is embellished with a pleated fabric band about two-and-a-half inches wide (Berko), finished with the small fabric rosette at the back. The skirt would have fit smoothly over the hips and been gathered at the centre back. Montgomery’s dress back would have fastened with hook-and-eye closures, and she probably required the assistance of cousin Frede to don her articles of clothing and jewellery for the wedding ceremony.

McBride noticed that inside the dress, some of the seam finishing had been sewn less professionally: for example, some half-inch seam allowances are turned one-quarter of an inch and held with “clumsy” running stitches, while others are inconsistent widths. Raw edges of the skirt’s layers had been placed on top of the tunic, and the waistband had been tacked, not neatly sewn, over top to conceal them (Documentation 5, 7, 10). Other seams had been pinked, and not stitched, to prevent fabric from fraying. The seamstress had no doubt been in a hurry to complete the extravagant gown in time for the early July ceremony, and less skilled workers may have assisted to complete hidden areas. There may have been extra costs incurred if the garment was rushed.10 Examination of other attire of the same or previous eras often points to hurried stitchery. In “Reconstructing Jane Austen’s Silk Pelisse, 1812–1814,” for example, Hilary Davidson notes that labour was the least expensive component of an article of clothing and using professional seamstresses or tailors in a time crunch did not promise an exquisite end result: “Some of the clumsiest stitching I have seen is the visible seams on the front of a pearl-embroidered silk bodice once worn by Princess Charlotte (1796–1817), only child of George IV (1762–1830). A reputable professional sewer presumably executed it, possibly in haste to fulfil the royal commission, yet ordinary garments show much neater and smaller stitching” (“Reconstructing” 210).

Examinations of two period wedding gowns and a waist held by the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation also show combinations of machine and hand stitching, with areas of imperfect stitching within all items. The waist, or bodice, of Mrs. T.G. Ives of Charlottetown, worn in September 1910, shows rough blanket-stitching to finish seams and large zigzag work behind the front lace, while the hem has been neatly machine stitched. The wedding gown of Eleanor (née Sharp) Long, circa 1910, is similar to Montgomery’s gown in that it used ivory net voile over light silk, with commercial lace. The design shares similarities with a high neckline, a small inset of lace at the neck, a pleated waistband, fabric roses, sleeve detail to the elbows, and lace to the wrist. A third item in the museum’s collection, discovered by McBride at a Salvation Army store, has several features that are similar to those of Montgomery’s gown—kimono sleeves, some pearl beading, steel-cut beading at the neckline, more skillfully executed fabric rosettes, and a pleated waistband. However, none of the textiles is as extravagant as the gown that Margaret Bulman created for Montgomery.11

As previously noted, Montgomery was comfortable spending money lavishly for fashions that she desired. In later years, she frequently commented on her fashion sense. For example, when a friend was holding an afternoon tea in her honour, she said in a 9 October 1919 journal entry, “I went through the motions gracefully—togged myself up in a French gown of shot pink and green taffeta and Honiton lace,12 which I don’t often get a chance to wear, strung some ‘gools’ on myself and pinned on the inevitable corsage bouquet and receiving smile” (CJ 4: 196). But her love of spending money on new fashions didn’t preclude Montgomery wearing her wedding dress if the occasion warranted. McBride points out that Victorian brides often wore their gowns to special events up to three months after their weddings (“Dress Codes” 37). Although Montgomery married in the Edwardian age, she continued to cling to some favourite Victorian traditions, including the etiquette protocol that allowed her to don her special dress. As documented in her journals, the wedding gown was worn for several other events throughout Montgomery’s lifetime, the first being her post-honeymoon reception in Leaskdale on 3 October 1911—two days under the three-month mark. Many years later, in a 12 February 1926 journal entry, she recalls “the night of our ‘reception’ when we came here after our wedding. I stood up then, a slim bride, wearing my wedding dress” (CJ 6: 16).

After the Leaskdale reception, at various times over the following three decades, Montgomery loaned out her dress as a historical costume for wedding tableaux. The first occasion was for a play performed in both Leaskdale and Zephyr Presbyterian churches, Ewan Macdonald’s two-point calling. On 10 December 1923, she records, “We ended up the play both in Zephyr and here with a very pretty tableau showing our two brides and their attendants. I got out my wedding dress and veil for Margaret Leask, who looked very pretty in it. My dress looks very nice still, only the cut steel trimming on it has turned dark” (CJ 5: 187).13 The second occasion was in Norval during one of the village performances, as noted in her journal on 24 February 1929: “We closed the programme with a tableau ‘Old Tyme Wedding.’ Alice Lesley wore my wedding dress and veil and nobody would believe I had ever been so slender. I could not believe it myself. I was very sorry to find that my veil, which is of silk tulle, is cutting badly. I wanted to keep it for Stuart—but I fear it will soon be in rags” (CJ 6: 249).14

Chesley Clark’s mother was apparently “disappointed” when she viewed the wedding gown at the Birthplace (possibly after the gown was purchased and displayed in the late 1960s) because she thought it had been altered (“Information”). Notes taken from a telephone call made by Rubio at the University of Guelph to the Confederation Centre on 30 April 1986 state that she was confident that no changes had been made to Montgomery’s wedding gown, since Rubio believed that the author's son Stuart Macdonald “was careful with such things” (K.R.). Although Montgomery commented on 10 December 1923 about the deterioration of her wedding gown when it was worn at a Leaskdale/Zephyr church function (CJ 5: 187), it seems that she may not have followed up with alterations. There was no mention by textile conservators regarding remodelling nor further documentation in her journals related to modifying the dress.

One Toronto resident, Linda (Olive) Watson, who attended the same parish that Montgomery did when she moved to her final home, Journey’s End at 210 Riverside Drive in Toronto, was thrilled to don Montgomery’s dress in a Sunday-school pageant featuring period wedding attire circa 1939. In Remembering Lucy Maud Montgomery, Alexandra Heilbron quotes Watson:

Here was a person who I thought was next to God and I was going to be wearing her dress! It had a very tiny waist and I fit into it ... I was five foot three and three-quarters and the dress was the right length ... There were stays that held my head up; there were stays around the middle to keep my waist straight. I couldn’t bend over; I couldn’t slouch. But I was proud to wear it." (168)

McBride was able to view these stays, or celluloid boning, on each side of the centre back, the sides, and the side seams. Edwardian gowns had offered women new freedoms from tight, hampering clothing, and often used lighter fabrics such as linen, cotton, and lace. As Watson stated, Montgomery’s gown was constructed from lace and silk but incorporated celluloid pieces to hold her upper body and neck stiffly upright without much freedom of movement. The celluloid body pieces were approximately five-and-three-eighths inches long and extended above the top of the waistband. The boning was not attached to the lining or outer silk, but “deeply embedded at the waistline so it stays put” (Documentation 11). The restrictive stays could have been a considerable part of the reason that Montgomery declared in another retrospective entry dated 2 July 1911 that she could not eat at her own wedding dinner, although she led us to believe it was her wretchedness over her marriage and loss of freedom at “that gay bridal feast.” “And I shall always think mournfully of that dinner—for I could not eat a morsel of it,” she notes. “In vain I tried to choke down a few mouthfuls. I could not” (CJ 2: 418).

Montgomery’s Extra (Extra) Small Size

Other than requests to see a photograph of Montgomery in her wedding gown, the most frequent question at the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace is, “Is that her actual size?” Elizabeth Epperly interviewed Kate Macdonald Butler, daughter of Montgomery’s son Stuart Macdonald, in 2000. She remembered playing dress-up with her grandmother’s wedding gown and shoes when she was young because the items of clothing were so tiny (11). McBride also notes the size early in her report: “Very tiny. First thing that hits you” (Documentation 2). There are no definitive measurements of Montgomery left behind in paperwork by diligent Edwardian dressmakers, but we can measure the form used to display her gown. Montgomery’s approximate measurements from the dressmaker’s form are bust thirty-one inches, waist twenty-three-and-one-half inches, hips thirty-six inches, and length from floor to shoulder tip fifty-five inches. Consulting current day Canadian size charts for various and popular brands of women’s clothing,15 at the time of her wedding Montgomery would have been what we would now call an XXS or perhaps XS.

In a journal entry for 13 December 1920, Montgomery says she wears size four shoes: “My feet are quite large in proportion to my size” (CJ 4: 286). In the twenty-first century, size four shoes for women are some of the smallest available. Clothes and shoes often vary in size from manufacturer to manufacturer and throughout the years, but in the over one-hundred years since Montgomery wed, people and their feet have generally increased proportionally (Walkezstore.com). In 1911, Montgomery’s foot size seemed to be in the average range, despite her stating that her footwear was large.

Manufactured by the Swiss luxury shoemaker Bally, a company founded in 1851 and still in operation in the twenty-first century, the wedding shoes in the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace are small and narrow and indicate size “3–4” on the sole. The sole stamp on Montgomery’s shoes shows that her footwear may have been purchased from the United Kingdom, as Bally shoes were not sold in Canada or the United States before 1923 (Bally), twelve years after her wedding. According to email correspondence that I had with a representative of the Bally Client Services Team, pumps similar to those Montgomery wore were “typically priced between 10 and 50 Swiss Francs (CHF),” but “the exact price may have varied depending on the location of purchase and whether the shoes were customized or part of a standard collection.” Since Montgomery did not visit the United Kingdom until after her wedding, she must have ordered the fancy shoes at considerable expense, plus shipping costs from overseas, to arrive in Canada in time for her nuptials.

Measuring the length of the dress and the approximate two-inch heels of her shoes, it seems that Montgomery may have been five feet one inch or five feet two inches in height. In a journal entry 13 December 1920, Montgomery states, “I am of medium height—about five feet five inches, but somehow usually impress people as being small” (CJ 4: 286). It is unlikely that her silk-and-lace dress would have shrunk through washing, if indeed it was ever cleaned at all after the ceremony; it would have been a challenging item to launder and conservation reports from 1986 note that it was quite soiled after Montgomery’s death (Burnham). Fashions of 1911 gowns often show a pooling of fabric at the front hem as well as the back, and Montgomery’s may have been a similar style (Oakes, “A Wedding Dress”), in which case the excess fabric would be subject to excessive dirt as it trailed along floors or the ground, or if it was accidentally stepped on by inattentive wedding guests. When Montgomery was first interviewed in Boston in 1910, she said the journalists found her “petite, with ... fine, delicate features,” as well as “slight and short—indeed of a form almost childishly small” (CJ 2 [29 Nov. 2010]: 328). Journalists’ reporting, McBride’s documentation, and Kate Macdonald Butler's memories of dress-up point to the author being shorter than she related.

Along with her wedding shoes, Montgomery’s size four and a half black slippers—part of her trousseau ensemble—are displayed seasonally at the Birthplace. The black velvet shoes were purchased from a Boston shoemaker, The Henry H. Tuttle Co. (TUTTLE is carved into the leather sole of one of them.) The impressive black-jet beading is appliquéed to the shoe tops with the same thread used on the edging of the shoes. Both the black and cream shoes are approximately nine inches in length and two-and-a-half to two-and-five-eighths inches wide. Because European measurements are slightly smaller than North American lengths, the size four and a half Boston shoes are proportionate with the size “3–4” wedding slippers from Switzerland.

In her journal entry for 9 September 1916, Montgomery claimed that she weighed 107 pounds, and “never went as low as that before” (CJ 3: 241). At that time, news regarding the First World War, household and church duties, her mental-health challenges, and two small children exhausted Montgomery. Yet, judging by comments in the press and the size of her wedding attire, she may have been a similar weight when she wed, perhaps due to the stresses and challenges presented at and after the time of her grandmother’s death, while sorting through personal effects, clearing out the house, and moving into the Park Corner home with her aunt and uncle. But she also had a fondness for walking, which would have kept her trim and fit.

In the extended description that Montgomery gives of herself in her journal on 13 December 1920, Montgomery notes that her hands are “exceedingly small” and that she wears “a 5¾ glove but could wear 5½” (CJ 4: 286). She does not mention gloves complementing her wedding dress, and none accompanied her personal effects. While it is possible that she wore a pair and removed them to allow Ewan to slip her wedding ring on her finger, fashion magazines of the era began to discuss the option of brides not wearing gloves, and many historic photos show that they did not (Oakes, “Real Brides”).16

The Gown’s Return to the Island

Beginning in 1967, Montgomery’s gown was displayed at the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace in New London after its sale by her son Stuart Macdonald. In a letter of acknowledgement dated 14 April 1967 from Frank Storey, general manager of the Confederation Centre, to Macdonald, Storey stated that numerous items belonging to Montgomery were forwarded to Lemuel Prowse of Prince Edward Island. Macdonald requested a purchase price of $2,000 for all of the items.

On 8 June 1967, Storey again wrote to Macdonald recognizing receipt of the items referred to in his letter dated 6 May 196717 and his enclosure of a cheque for full payment of the goods. In turn, Macdonald acknowledged receipt of Storey’s letter and confirmed that payment was received on 10 June 1967 for his mother’s wedding dress and shoes,18 scrapbooks, the original manuscript of Anne of Green Gables, her diploma from Prince of Wales College, and “other manuscripts.” The Birthplace contributed $500 toward the purchase.19 A faded handwritten note on the back of her calling card that Montgomery provided with the slippers provides further provenance for the items.

Conservation and Reproduction

After the dress had been displayed for nearly twenty years in New London, in 1986 conservation work was proposed by Eva Burnham, chief of the textiles division at the Canadian Conservation Institute in Ottawa, with an anticipated timeline of three-hundred hours. Burnham reported the condition of the dress as fair; there were stains, tears, and fragile areas. The six short plastic or celluloid stays that provided discomfort for Linda Watson in the late 1930s had penetrated the stand-up collar. As well, the taffeta lining in the bodice was extremely fragile with “large areas missing” (Burnham).

Burnham’s proposed treatment consisted of preparation for dry and/or wet cleaning and surface cleaning to remove accumulated dust and soil. Among the many repairs, she proposed that a tear along the beaded edge be backed with a matching material (not specified, but possibly a chiffon net), and the lace insert in the bodice amended by the insertion of a new piece of crepeline behind the lace. She recommended that the stays be removed and covered with matching material (also possibly a chiffon net) to protect the lace collar, and the missing lining in the bodice replaced, although she did not specify with what.

Montgomery’s tulle veil was torn, soiled, and discoloured. The faux orange blossoms were fragile, “particularly the spray at the center back where many of the blossoms have cracked and parts of the wax are broken off” (Burnham). Burnham suggested that the orange blossoms be removed to allow the veil to be cleaned and the blossoms treated with micro-crystalline wax and mineral spirits to seal the cracks. The ivory wedding shoes were in fair condition but with some staining and distortion in the bows. The shoes would be surface cleaned, the worn left heel rematched with new silk, and the bows steamed into shape and stabilized. The black velvet shoes were in good condition, Burnham reported, albeit in need of a surface clean.20

Burnham’s conservation work was completed in 1986, and the dress was again displayed seasonally at the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace. Yet despite the reconditioning and repair, Montgomery’s gown continued to deteriorate over the subsequent two decades. Linda Berko discussed the condition in a letter to Kevin Rice dated 11 December 2000. The silk taffeta in particular suffered “extensive shattering and splitting ... from top to bottom, especially along pressure points at hip and waist.” Because the dress was removed seasonally from the mannequin and stored in a textile box at the Confederation Centre, “the weight of the beading, the weakened state of the artifact and the constant mechanical movement involved when removing the dress from the mannequin has contributed to the deterioration of the garment,” Berko observed. She believed that the dress should be safely stored in an appropriate container and fully stabilized and recommended that a reproduction gown be fabricated for display purposes. Although the Birthplace has a purpose-built display case, Rice confirmed in a letter dated 17 April 2003 to Father F.W.P. Bolger that for preservation reasons Montgomery’s gown would be permanently archived when the Birthplace closed after the fall season of 2003.21 While the original gown was stored in an appropriate container with adequate support and buffering material, and in proper environmental conditions (20˚C, RH 45–55%), further stabilization22 was not undertaken.

In “The Embodied Turn: Making and Remaking Dress as an Academic Practice,” Hilary Davidson contends that experiential dress knowledge can be known as the “embodied turn,” or discovery through the processes of “doing, making and remaking, and reconstructing as a fruitful methodology with quantifiable, academically valid results” (329). Further, the “material turn” allows historians to recognize that textile objects are as vital to historical research as image and textual sources, which is “an understanding long established in archaeology and museology.” Historical scholars can incorporate “embodied, experiential, implicit or tacit knowledges gained through making and doing into their study of history” as the word embodied “also refers to the innate body knowledge created through making objects” (330). In 2002, a replica of Montgomery’s wedding dress was in progress by A.B. White of Whiteworks, Winsloe, Prince Edward Island, after research was undertaken by McBride. White recalls the extreme fragility of the gown while making its replica: “My impression of being close to it was, you wouldn’t want to sneeze near that dress or it would end up as a pile of silk on the floor.”

In her analysis of the dress, McBride notes that the textile displays “softness and lightness,” offering “wonderful insight into what Lucy Maud Montgomery was like” (“Works”). White handcrafted a dress form to hang the new gown, using measurements obtained directly from the original outfit as calculated by McBride. The replica fabric was primarily silk, which White ordered from Toronto, and a firm in Montreal did the pleated taffeta under-pieces (White). White did some of the hand-beading herself; she recalls making samples using a tambour method23 and assembling the finished parts on the gown. She sewed most of the body of the replica by machine.

Images of wedding gowns from 1911 show the cylindrical silhouette and simpler drape were the height of fashion for many brides, and the gowns of wealthier women were adorned with extensive beading like the author’s (Oakes, “Real Wedding Dresses”). Montgomery’s tastes were modern, but because she was in her mid-thirties and marrying a minister, she did not attempt any radical fashion looks such as a low, open neckline or bare arms.

Conclusion: Reading Absences

Dress historian and curator Hilary Davidson argues that “[r]emaking historic dress is a way for dress historians and fashion scholars to engage with the many material and cognitive absences our understanding of the clothed past is predicated upon,” such as “surviving examples, dye colors, fibers, construction techniques.” She then goes on to remark:

Close investigation of dress requires filling the gaps, conjecturing or reading absence into incomplete presents. Reconstruction creates new garments that tell us about past ones in unique ways, and reiterates how sewing and construction are essential to fashion systems fundamentally enmeshed with material culture." (“Embodied” 332)

Artifacts such as Montgomery’s gown often degrade or are made into another form after wearing, such as Montgomery’s mother’s wedding dress of 1874, which, as Montgomery sadly recounts in a journal entry for 29 December 1921, was cut apart (CJ 4: 359–60). Her grandmother “ripped it to pieces and discarded everything but the sleeves and skirt breadths” so that the vivid green silk could be remade into a dress for Montgomery. However, the brilliant colour became unfashionable and the fabric remained stored in a trunk. After her move to Leaskdale, Montgomery used the silk to sew two petticoats for herself and felt closer to her mother through the crafting and reminiscing but lamented that the original wedding gown was cut apart: “I would give much if I had that dress today just as it was. It would be a valuable heirloom” (CJ 4: 359). To have a small portion of Montgomery’s material culture more than one-hundred years after her wedding has been a boon to historians, particularly those involved in textiles, and has offered a window into her personal life and times.

Montgomery was justifiably proud of her trousseau. Without parents or grandparents to offer gifts or support at her wedding, Montgomery assured her family and friends that she was able to take charge of her own life and finances to create a romantic, fairy-tale celebration. After the Macdonalds’ wedding ceremony and her second wearing during a 1911 address at St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church in Leaskdale, several church tableaux, children’s dress-up games, and over three decades of display at her birthplace, the fragile wedding gown rests in an archival box under carefully controlled conditions in the Confederation Centre Art Gallery. The repast may have been homemade, and the intimacy of close family and friends with the wedding couple in the parlour kept it modest, but her attire and honeymoon arrangements were, as Prospero says in Shakespeare’s The Tempest (4.1.156–57), the “stuff / As dreams are made on” for most Island brides.

Montgomery commissioned an expensive gown of fine silk, symmetrically balanced with repeated beaded bands and medallions, lace insets, and pattern motifs that proclaimed her personal fashion statement. While a replica offers visitors at the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace a visual concept of the original, the richness of the real Edwardian gown is a striking display of her new wealth and her growing confidence in her literary fame and place in society, and an opportunity to indulge in the sumptuous clothing that she loved.

Bio: An independent researcher, Deborah Quaile has worked at the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace in New London, Prince Edward Island, as docent and manager. She wrote and edited seven local history books in Ontario, including L.M. Montgomery: The Norval Years, 1926–1935. She has also published in The Shining Scroll, with the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, and presented at the L.M. Montgomery Institute’s 2024 conference on Montgomery’s birthplace. Instagram: @debquaile1

Acknowledgements: I am grateful for the assistance of Kathleen MacKinnon for access to Montgomery’s wedding attire, photography, and the files at the Confederation Centre of the Arts; Meg Preston at the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation for sharing the collection’s period textiles; Simon Lloyd at Robertson Library, UPEI, and the fonds of Sheri McBride; Archival and Special Collections, University of Guelph, for digital images from the L.M. Montgomery Collection; A.B. White, creator of the lovely replica Edwardian gown displayed at the Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace each summer; Terry Kamikawa for information, photographs, and access to the Japanese replica wedding gown; and Sheilagh Quaile, Elizabeth Epperly, Alexandra Heilbron, Denise Bruce, David Macneill, Mary Beth Cavert, and Arnold Smith for their thoughts, information, and encouragement.

- 1 Presented as a flashback from a long “catch-up” journal entry dated 28 January 1912.

- 2 A waist is a blouse or shirt, possibly embroidered, with a collar and cuffed sleeves.

- 3 The sewing machine is now in a private collection in Prince Edward Island.

- 4 Soie is the French word for silk. Crepe is a light fabric with a slightly wrinkled surface. Montgomery’s double use of the word “silk” and the French description “crepe de soie” may seem overly pretentious.

- 5 Similar veils and gown can be seen under “A Page for Brides,” Women’s Home Magazine, 1911, https://thedreamstress.com/2011/12/a-wedding-dress-of-1911/.

- 6 In this letter, Rubio notes that “[a]s a general rule, LMM did not photograph or keep pictures of people or places which made her unhappy.”

- 7 The lily of the valley did not survive in Montgomery’s personal scrapbook at the University of Guelph Archive. Oddly, the white ribbon around the pressed flowers and fern is printed with “Merry Christmas” and sprigs of holly.

- 8 When Montgomery’s grandmother Lucy Macneill died, Montgomery was intent on ensuring there would be the varieties of flowers her grandmother loved to fill her parlour and casket. Montgomery therefore ordered some to be delivered from a florist, possibly in Charlottetown or Summerside, in early March 1911 when nothing bloomed in a late Cavendish winter. Recalling this scene in a journal entry for 28 January 1912, Montgomery writes, “in the darkening parlor grandmother lay at rest ... and all about her the whiteness and sweetness of the flowers I had sent for ... I was determined that she should have them about her in death and that they should be laid close around her face in the grave” (CJ 2: 375).

- 9 In Documentation of L.M. Montgomery’s Wedding Dress, McBride suggests the beaded bands to be in “an abstract floral/paisley pattern,” but I believe the forms continue the rose theme with flowers and leaves.

- 10 To date no paperwork detailing costs of any of the wedding gowns—Montgomery’s original from 1911, a replica from 2003, or a Japanese replica from circa 2010—has been found to compare historical pricing, nor for her wedding slippers and black trousseau shoes.

- 11 The three items in the collection of the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation do not have any accompanying accessories, such as gloves, shoes, headbands and veils, or hats. Ivory seems to have been the popular fashion colour, since all items used ivory silks, muslin, lace, beading, threads, and voile. Provenance of HF.93.1.1 is unknown.

- 12 Honiton lace has historically been crafted in the town of Honiton, England, and enjoyed a particular popularity during the reign of Queen Victoria, who used the handcrafted bobbin lace on her wedding gown and other attire through the years. As well, the next royal, Queen Alexandra, later asked attendees at Edward VII’s coronation to wear British-made goods, and Honiton lacemakers received many orders for women’s trimmings. Information is from Brittany Van Dalen, “Honiton Lace,” Historic UK, www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Honiton-Lace/.

- 13 The cut-steel trimming refers to small silver-toned beads.

- 14 The fine tulle was subject to tears. Montgomery’s desire to hold on to her wedding attire for her second son is understandable, since she did not have a daughter to whom she could pass on her gown for a possible second wedding wearing. Stuart Macdonald kept his mother’s gown, shoes, and veil, but sold them in 1967 so that they would have a permanent home in Prince Edward Island.

- 15 I consulted aprilcornell.ca, merrell.com, and tilley.com.

- 16 None of the gowns in the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation collection have gloves accompanying them.

- 17 No copy of the 6 May 1967 letter is available.

- 18 There is no record of gloves to accompany the wedding gown, veil, and shoes in Montgomery’s journals or in the list of purchased effects from the Confederation Centre. However, the photograph she pasted into her journal of Anita Marcone, a socialite and her new husband who were also visiting Montgomery’s publisher L.C. Page in Boston, shows long gloves with Marcone’s lacy wedding dress (CJ 2 [29 Nov. 1910]: 325).

- 19 The Lucy Maud Montgomery Birthplace financial archive contains a 1967 cancelled cheque for that amount.

- 20 What appears to be red Prince Edward Island dust on the black shoes’ beading can still be seen under magnification.

- 21 The gown’s accession record is “Bulman, Margaret (Cavendish, PE). L.M. Montgomery's Wedding Dress and Veil, c. 1911 silk satin, silk tulle, lace, chiffon net, pearls, white beads and rhinestones. Purchased, 1967. Collection of Confederation Centre Art Gallery, CM 67.5.21 a,b.”

- 22 Berko’s cost estimate was $3,000 plus materials for the gown’s stabilization in 2000.

- 23 The tambour method uses a small hook, like a miniature crochet hook, to create a chain stitch to fasten beads. The method gives a neat and secure finished product, but it does require both hands, and, therefore, the light fabric is held in a hoop or frame. Once an embroiderer is comfortable with the stitching and beading, the process is said to be quite speedy for applying thousands of beads of all sizes. Information is from the Embroiderers’ Guild of America, “Introduction to Tambour Embroidery for Cosplay,” Louisville, Kentucky, 17 July 2023, https://egausa.org/introduction-to-tambour-embroidery-for-cosplay/#:~:t….

Works Cited

Bally Client Services Team. “Re: Bally's history and its potential connection to the renowned Canadian author L.M. Montgomery.” Received by Deborah Quaile, 10 June 2024.

Berko, Linda. Letter to Kevin Rice, 11 Dec. 2000. “Lucy Maud Montgomery Wedding Dress Treatment Proposal,” Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

Burnham, Eva. “Wedding Dress, Veil and Shoes,” Examination and Treatment Proposal, #2004770, 11 Mar. 1986. Canadian Conservation Institute, National Museums of Canada.

Davidson, Hilary. “The Embodied Turn: Making and Remaking Dress as an Academic Practice,” Fashion Theory, vol. 23, no. 3, 2019, pp. 329–62.

---. “Reconstructing Jane Austen’s Silk Pelisse, 1812–1814,” Costume, vol. 49, no. 2, 2015, pp. 198–223.

Epperly, Elizabeth. “Ten Years Later: An(other) Interview with Cousins Dave and Kate Macdonald.” Kindred Spirits, Spring 2000, pp. 10–11.

Heilbron, Alexandra. Remembering Lucy Maud Montgomery. The Dundurn Group, 2001.

“Information from Chesley Clark, Rusticoville.” Unsigned handwritten note, March 1986. Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

Johnstone, Archibald Hynd. Lucy Maud Montgomery Remembered. Hear to Serve Publications Inc., 2005.

Jorgensen, Kathy. “Centre Seeks Photographs of Lucy Maud Wedding Gown.” [Charlottetown?].

K.R. [Kevin Rice?]. Handwritten note for telephone interview with Mary Rubio, 30 Apr. 1986. Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.

“The Marriage of Miss Lucy Maud Montgomery … to Rev Ewen McDonald [sic].” The Charlottetown Guardian, 5 July 1911, p. 5.

“The Marriage of Miss Lucy Maud Montgomery to Rev. Ewen McDonald [sic].” The Charlottetown Guardian, 8 July 1911, p. 7.

McBride, Sheri. Documentation of L.M. Montgomery’s Wedding Dress. Robertson Library, University Archives and Special Collections, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown.

---. “Dress Codes: The Etiquette of Dress in 19th Century Charlottetown.” Island Magazine, no. 48, Fall/Winter 2000, p. 31–38.

---. “Labels” for Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Wedding Dress (Note to Kevin Rice received 4 June 2006.). Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown.

---. “Works: Wedding Dress.” The Bend in the Road: An Invitation to the World and Work of LM Montgomery. CD-ROM 2000. L.M. Montgomery Institute, University of Prince Edward Island.

Montgomery, L.M. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901–1911. [CJ 2]. Edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston, Oxford UP, 2017.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1911–1917. [CJ 3]. Edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills Press, 2016.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1918–1921. [CJ 4]. Edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills Press, 2017.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1922–1925. [CJ 5]. Edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills Press, 2018.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1926–1929. [CJ 6]. Edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills Press, 2017.

---. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1985–2004. 5 vols.

Moore, Heather. “Sewed Wedding Dress for Lucy Maud Montgomery.” The Eastern Graphic, 24 Sept. 1975.

Oakes, Leimomi. “Real Brides of 1911.” The Dreamstress, 10 Dec. 2011, thedreamstress.com/2011/12/real-brides-of-1911. Accessed 7 June 2024.

---. “Real Wedding Dresses of 1911.” The Dreamstress, 7 Dec. 2011, thedreamstress.com/2011/12/real-wedding-dresses-of-1911. Accessed 22 Oct. 2024.

---. “A Wedding Dress of 1911.” The Dreamstress, 5 Dec. 2011, thedreamstress.com/2011/12/a-wedding-dress-of-1911. Accessed 18 July 2024.

Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation. Accession numbers HF.72.137.2, gown, Mrs. Eleanor (Sharp) Long; HF.89.73.4, waist, Mrs. T.G. Ivor; HF.93.1.1, gown found by Sheri McBride.

Reddy, Karina. “Fashion History Timeline, 1910–1919.” Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York, updated 18 Aug. 2020, fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1910-1919. Accessed 13 Sept. 2024.

Rice, Kevin. Letter to Father F.W.P. Bolger, 17 Apr. 2003. Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown.

Royal Household. “Royal Wedding Traditions: Orange Blossom,” https://www.royal.uk/royal-wedding-traditions. Accessed 2 July 2024.

Rubio, Mary. Letter to Kevin Rice, 12 Feb. 1986. Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown.

---. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Doubleday Canada, 2008.

Rubio, Mary, and Elizabeth Waterston. Introduction. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery, Volume 2, 1910–1921, edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterson, OUP, 1987, pp. ix–xx.

Shakespeare, William. The Tempest. William Shakespeare: The Complete Works, edited by David Bevington, updated 4th edition, Longman, 1997, pp. 1060–116.

Storey, Frank J. Letter to Stuart Macdonald, 14 Apr. 1967. Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown.

---. Letter to Stuart Macdonald, 8 June 1967. Collection of the Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown.

Walkezstore.com. “It’s a Fact—Our Feet Are Getting Bigger,”walkezstore.com/blog/2014/07/19/its-a-fact-our-feet-are-getting-bigger/#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20in%201900%2C%20the,wears%20around%20a%20size%209. Accessed 7 June 2024.

White, A.B. Telephone interview by the author. 26 Mar. 2024.

William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, MI. “So Once Were We”: Death in Early America—Mourning Fashion, https://clements.umich.edu/exhibit/death-in-early-america/mourning-fashion/. Accessed 3 Sept. 2024.

Woods, Hannah Rose. “Ruffles, Frills and Smoking-Hot Suffragettes: The Art of Edwardian Fashion.” Art UK, 2 Apr. 2020, https://artuk.org/discover/stories/ruffles-frills-and-smoking-hot-suffragettes-the-art-of-edwardian-fashion. Accessed 2 July 2024.