This essay examines the peculiar history and reception of L.M. Montgomery’s Pat books in Japan, where the sequel was published first and the first volume was long unavailable. Consequently, for nearly twenty years, Japanese readers could not fully appreciate the theme of loss and new life in the Pat books.

Introduction

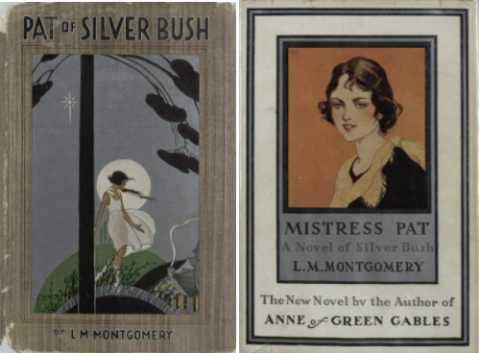

“I gave Anne my imagination and Emily Starr my knack of scribbling; but the girl who is more myself than any other is ‘Pat of Silver Bush’—my new story which is to be out this fall. Not externally but spiritually, she is ‘I,’” wrote L.M. Montgomery in her letter to Roberta Mary Sparks, a young fan in Saskatchewan, on 4 July 1933.1 Citing this passage in her biography of Montgomery, Mary Henley Rubio states that “Pat was her [Montgomery] at this point in her life”; that is, in the author’s late fifties, when she lived in Norval and suffered from many domestic pressures. Compared with Montgomery’s Anne books and the Emily trilogy, the Pat books—Pat of Silver Bush (1933) and Mistress Pat (1935)—have received little attention in Montgomery studies. In The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass, Elizabeth Rollins Epperly classifies the Pat books in Part III, “Other Heroines,” with Jane of Lantern Hill,2 and in his book list of Montgomery’s novels, Benjamin Lefebvre groups them similarly, under “Other Books.”3

However, the Pat books have special appeals: one of them is the connection to their author’s life because, as Heidi MacDonald states, “Montgomery based much of the Pat novels, unconsciously or not, on the very difficulties and frustrations she experienced while writing them in the early 1930s.”4 Compared to the sunny Anne series, the Pat books are much darker and explore the solemnity of loss from a mature point of view. They are worth more attention in Montgomery scholarship to unveil their peculiar relationships with the author’s agony of loss and her creativity in her later life.

That Montgomery’s writing connects to her life should be no surprise to Montgomery scholars. Researchers have documented how, in her later life, Montgomery found writing to have a therapeutic effect. As Rubio points out in her biography The Gift of Wings, “In the Norval years, the act of writing moved from being a source of pleasure to therapeutic activity.”5 Melanie Fishbane’s article “Writing as Therapy in Rilla of Ingleside and The Blythes Are Quoted” maintains that “Writing provided a means to channel her [Montgomery’s] darker moods and doubts about self and society.”6 Further, Mary Beth Cavert reflects on writing as release in her article on Montgomery’s Leaskdale years and her experience of loss in the Great War, that Montgomery’s “commemorative journaling about Frede is an enduring lament of her loss.”7 When Pat of Silver Bush was first published, Montgomery wrote in her journal (on 1 August 1933), “It seemed to me such an ‘escape’ while I was writing it,” suggesting that to her, writing Pat was an escape from the harsh reality of life.8

Thematically, the Pat books are generally regarded as depicting Patricia Gardiner’s strong attachment to her home. The two novels, Pat of Silver Bush and Mistress Pat, centre respectively on her growth from seven to eighteen and twenty to thirty-one. Pat’s deep affection for her house, Silver Bush, increases after she starts losing the people important to her, so the eventual loss of her beloved house devastates her. In my personal reading experience, which includes reading the Pat books in my late teens, I consistently considered them to be novels of loss, in that Pat grows up to experience loss again and again: the death of her best friend, Bets Wilcox; the long absence of Hilary “Jingle” Gordon after he leaves Prince Edward Island to attend university in Toronto; the separation from her brother and sisters who leave home for work or marriage; the death of Judy Plum, the family’s Irish housekeeper and Pat’s mother-substitute; and finally, the loss of her beloved home to fire. However, because my reading of the books was disrupted by their peculiar translation history, it was not until I was able to reread the books in their intended order that I fully comprehended the meaning of loss to Pat. “Loss” in the Pat books and in this article encompasses all four distinct meanings found in the Oxford English Dictionary. “Loss,” that is, “[t]he fact of losing,” is (1) “being deprived of, or the failure to keep (a possession …); (2) “loss of life”; (3) “being deprived by death … of (a friend, … a person regretted)”; or (4) “[f]ailure to gain or obtain.” “Loss” in the Pat books is contrasted with “regeneration,” which is “the action of coming or bringing into renewed existence,” and “resurrection,” which, besides “[t]he rising of Christ from the dead,” refers to “[r]evival or revitalization, especially of a person who … has fallen into inactivity. …”9

Although the Pat books are filled with many losses, they also constitute a story of “building up a new life,” to use Montgomery’s own phrase in Mistress Pat.10 That is, while the loss that thematically pervades the books has its roots in Montgomery’s own life, in these novels she is able to recreate and sublimate her experience of loss and produce hope for a new life at the end. While writing the Pat books, Montgomery had several worries: asthma, insomnia, her husband’s severe depression, the pressure to earn a living, and her first son Chester’s secret marriage. Montgomery seems to have expressed her hope for regeneration through fiction, wishing for a better end of her life. In particular, the ending of Mistress Pat shows that only after Pat loses everything can she escape her depression and start living again. Through the brief reversal at the end, this book suggests that even from loss and emptiness we can gain something new and essential.

However, this important point was lost to Japanese readers of the Pat books due to the out-of-order publication of the Japanese translation: many Japanese readers first read the sequel, Mistress Pat, in 1960, then could only read an abridged version of the first book, Pat of Silver Bush, in 1974; they could not access its complete translation until 1981. Readers in Japan discovered Pat’s fate before they had the opportunity to read about her girlhood, and, therefore, they experienced the story’s narrative arc in incomplete and unfulfilling ways. By examining the origins and the consequences of Montgomery’s first Japanese translator’s decision to translate the sequel first, this paper explores not only the fractured reading experience that prevented readers from fully understanding the powerful theme of loss and new life in the Pat books but also illustrates how the experiences of the readers and translators echo those of Pat and Montgomery in their journeys from loss to regeneration.

Publishing the Pat Books Out of Order

On 15 January 1934, Montgomery wrote in her journal, “Today I began work on a sequel to Silver Bush.”11 Because she had not decided on the title yet, she refers to the sequel as Pat II in her journal,12 but it seems that Montgomery wrote this novel assuming her readers had already read Pat I.13 While the chapter titling style of the two books is different, Mistress Pat is clearly a sequel to Pat I.14

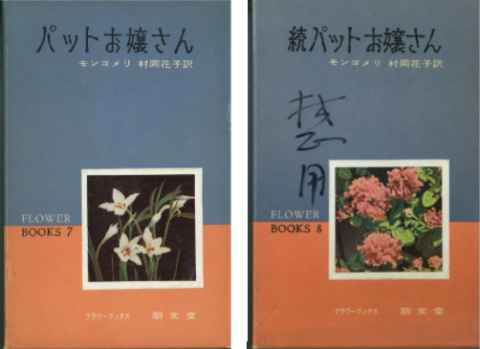

Despite Montgomery’s intended sequence, in Japan a curious reversal in the publication order occurred: the second volume, Mistress Pat (Pat II), was first translated and published in Japanese in 1960,15 while an abridged version of the translation of the first volume only appeared fourteen years later, in 1974.16 Moreover, Japanese readers had to wait six additional years to read the complete translation of Pat of Silver Bush (Pat I), which appeared in two volumes in 1980–1981.17 This meant that Japanese readers could not fully read Pat of Silver Bush for nearly twenty years, despite having access to the sequel. I argue that this unexpected order of publication greatly influenced the reading experience for Montgomery’s Japanese audience and still holds a certain impact on them. For example, still in 2016, Anemu, an avid reader of Montgomery, wrote that one of her biggest regrets in life is that she read the Pat books out of order.18 What happened? Why were the novels published out of order in Japan?

Japan is a country where translation is very prevalent; Japanese readers tend to read foreign books in translation. The structure of English is so different from Japanese that without special training it is difficult for even Japanese who read English to comprehend novels written in English due to literary expression and rich vocabulary. This means that only a limited number of Japanese readers can appreciate Montgomery’s books in their original form. Thus, since publication, most Japanese people have and do read Montgomery’s works in translation.

Right: Book cover of Zoku Pat Ojousan [Mistress Pat sequel]. 1960. Japanese translation by Hanako Muraoka. Flower Books 8. Hobundo. Image courtesy of Toyo Eiwa Jogakuin Archives.

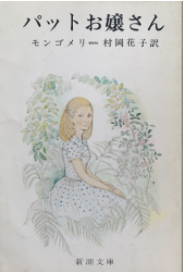

Mistress Pat’s translator, Hanako Muraoka, began translating Montgomery with Anne of Green Gables, which was first published in Japan in 1952, and so she became established as Montgomery’s Japanese translator. The novel awarded Montgomery a large following in the country and led to further books from the Anne series being translated and published almost sequentially.19 Although Muraoka’s original translations were sometimes truncated, as had been the custom for translation in Japan since the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until about the 1950s,20 Muraoka continued to produce high-quality, readable, lyrical translations. The quality of her translations is one of the reasons for Montgomery’s enduring popularity in Japan. In response to the high expectations of her loyal readers, who were eagerly awaiting Montgomery’s books, Muraoka published her translation of Pat Ojousan [Mistress Pat] as a two-volume hardcover edition by Hobundo on 30 March 1960, eight years after Anne of Green Gables was published in Japanese. In 1965, it was published in Shincho Bunko paperback series and circulated widely.

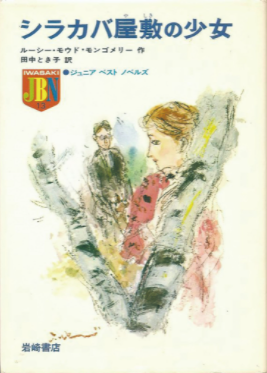

In 1974, after Muraoka passed away, another translator, Tokiko Tanaka, Muraoka’s student and former assistant, published an abridged translation of Pat of Silver Bush under the different title Shirakaba Yashiki no Shoujo [The Girl of Silver Birch House]. As one part of a translation series aimed at students from ten to fifteen years of age, the book had a page limitation. Therefore, this translation follows the main plot but omits ten out of thirty-nine chapters, including the scene where Pat dances in the moonlight, along with Montgomery’s descriptions of nature and Judy’s conversations. These omissions make it difficult for readers to experience Pat’s peculiarity as well as the humour, atmosphere, and flavour of the original work.21 Moreover, Tanaka writes in the last paragraph of her “Translator’s Afterword,” “This translation is incomplete, so I hope to upgrade it into a complete version in the future,” which reinforces Muraoka’s avid readers’ frustration about this book.22 The Girl of Silver Birch House was published by Iwasaki Shoten, a different publisher than the one who published the translation of Mistress Pat. Since the name “Pat” was intentionally excluded from the book’s title, and this book was published as one of a series of translations of twenty unfamous books, few readers could recognize this abridged version as Pat of Silver Bush. In fact, I did not notice the publication of this book at all until a younger Montgomery translator, Yumiko Taniguchi, mentioned it in her “Translator’s Afterword” in 2012.23 Tanaka made the translated text more readable for children by extensively using Japan’s simple, phonetic hiragana alphabet, so both its atmosphere and impression are very different from Muraoka’s translation of the sequel. In Tanaka’s “Translator’s Afterword,” she thanks one of the series translators, Shigeru Shiraki, for helping her to finally get the book published, so we can assume that she wanted to publish it in any format she could, even though it was just an abridged version of the book and in a children’s book series.

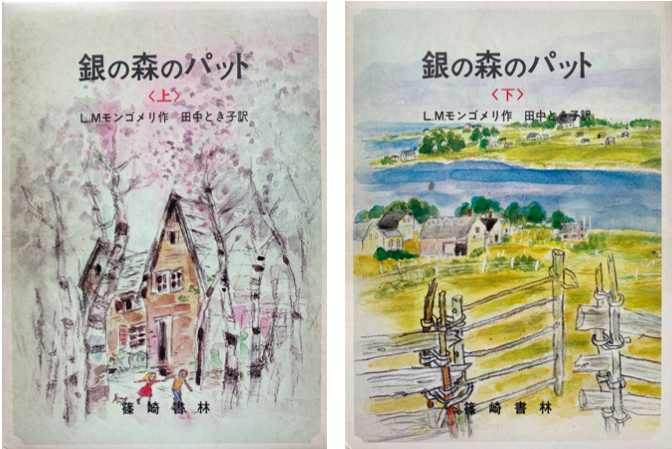

Right: Book cover of Gin no Mori no Pat (ge) [Pat of Silver Bush 2]. 1981. Japanese translation by Tokiko Tanaka. Cover illustration by Sachiko Yamanaka. Shinozaki Shorin.

It was not until the publication of a complete translation of Pat of Silver Bush that the puzzle of why Mistress Pat was published first was solved. Tanaka carried out a complete translation of Pat of Silver Bush in 1980–1981, and she finally disclosed the issue in her “Translator’s Afterword”:

Mrs. Muraoka had searched for a copy of Pat of Silver Bush through every means, but because the book was out of print at the time, she could not obtain a copy. So, she had to publish Pat Ojousan [Mistress Pat] first.

However, soon after she passed away in 1968, a retired professor from my university, Tokyo Woman’s Christian University—Miss Constance Chapel—found books written by Montgomery, which were out of print then, at a second-hand bookstore in Toronto, and kindly sent them to me. … Among them was this Pat of Silver Bush.24

Thus, it appears that this generous gift from her professor allowed Tanaka, at last, to translate and publish both the 1974 abridged version of Pat of Silver Bush and, finally, the complete version published in a two-volume hardback edition in 1980–1981 and paperbacks in 1983 by Shinozaki Shorin. This publisher later went out of business, so the complete version of Pat of Silver Bush was only available for a limited time and was missed by some Montgomery readers; even today it is not easy to obtain this version due to its being out of print.25

In short, Japanese readership and translation heavily depended on access to the original books, and the lack of accessibility is why the Pat books were published out of order. It must be borne in mind that it was extremely difficult for the Japanese to access books from Canada in the 1950s, during the aftermath of Japan’s defeat in the Second World War.

The Effects of Reading the Pat Books Out of Order

What were the consequences of this disorder for the Japanese readership? In “Reading In and Out of Order: Living In and Around an Extended Fiction,” Margaret Mackey asks: “How do such conditions of access affect our intimate responses to books?”26 She answers convincingly, based on her own reading experience; she read the Pat books in order but read the Anne books and the Emily trilogy out of order: Emily of New Moon (1923) first, Emily’s Quest (1927) second, and finally, many months later, Emily Climbs (1925). Thus, she knew the episodes and the ending of the Emily trilogy before she read the second book. This happened because, in her childhood, cheap paperbacks were not available, and children had to borrow expensive hardbacks from libraries or other owners; thus, she had no choice but to read whatever she could access, regardless of series order. Mackey pointed out that this still happens among contemporary readers.27

As a result of this situation, Mackey experienced two positive effects. First, she says: “My disjointed reading of the Montgomery books, satisfying and engulfing as they were in most other respects, caused me never to lose sight of the fact that this intriguing world was made by someone … as a composed work.”28 She states further: “As a consequence of this erratic access, however, I acquired some compensatory skills. I got better at creating some semblance of the larger narrative arc through the process of extrapolation and guesswork.”29 This statement endorses Wolfgang Iser’s assertion in The Implied Reader: “The need to decipher gives us the chance to formulate our own deciphering capacity.”30 I concur with Mackey’s idea that this random order of reading has these positive aspects, from my own experiences of reading the Borrowers series by Mary Norton—I read the first volume, and then jumped to the third volume because the second was unavailable. This made me aware that this was a world completely controlled by the author. I had to compensate for the loss of access to the middle book by guessing and making up new episodes to fit into the story’s larger narrative arc.

Nevertheless, Mackey writes further about the negative aspects of out-of-order reading that “[t]his higgledy-piggledy access introduces a whole new category of gaps, large, random, and annoying.”31 Mackey elaborates on her own experience of reading the Emily trilogy out of order, reading volume one, then three, then two:

I remember Emily’s Quest as a particularly aggravating read (ecstatic as I was to find it on my grandmother’s bookshelf), because of its regular references to the unknown events of Emily Climbs. I have reread these three titles many times since, and always in the correct order, but I have never erased the traces of my frustration on that first read; to this day, I recognize elements that once I did not know but needed to know, and I am invariably thrown out of the story by this recollection.32

Mackey’s reminiscence reflects the powerful effect of the reading experience on readers and, particularly, the potent and indelible impact of the first reading. She continues, “Yet there is no doubt that the gaps chafed.”33 I will focus on this “chafing” effect from here forward.

My initial experience of reading the Pat books out of order in the 1980s was very similar to Mackey’s. I started Mistress Pat first, without realizing that there was a prequel because only Mistress Pat was translated in Muraoka’s paperback series, which was widely circulated in Japan in those days. After I started reading, I noticed that something was amiss. First, Pat is already a grown woman—twenty years old when the novel begins—which is uncharacteristic of Montgomery’s books, which are generally about a girl growing up. Second, I had to ponder, who is Hilary Gordon? At the beginning of Mistress Pat, Hilary is already out of sight: “Hilary Gordon had left him [his dog] with Pat nearly two years ago, when he went away to college in Toronto.”34 Hilary appears mainly in his infrequent letters to Pat, who explains their content briefly to her family. The omniscient narrator supplements Pat’s brief reports to the reader with statements like: “She didn’t want Hilary Gordon for anything but a friend but she did not exactly warm to the idea of that [Hilary’s] ‘lucky girl’ whoever she was.”35 This description of Hilary is short and only implies that Pat likes Hilary, but that she is neither conscious of a deeper feeling nor admits to it because she wants to remain his friend. Hilary never physically appears in the novel until after he has been absent for ten years. His appearance occurs on page 420 of the 493 pages translation, which makes the readers’ guesswork to fill in the gaps quite a frustrating task.

As Mackey had read volume one of the Emily series first, at least she could understand the characters, their relationships, and their background; she acquired a solid base for understanding and guessing adequately. In this sense, my experience of reading the Pat books was more perplexing than hers reading Emily. Reading volume two first, I had little information about the characters, their relationships, or the background, which I should have obtained from volume one, and, therefore, I had to speculate. Although Montgomery gives readers the minimum information, guessing the missing parts was a kind of mental exercise that did not make for a very satisfying reading experience.

As I read onward, the number of perplexing parts of the novel started to mount, along with my general confusion. Already in the first chapter, which has 142 pages in the translation, a series of conversations between Pat and Judy recollects old memories. The first example occurs when Pat asks, “Judy, do you remember the time you sent us to her to witch McGinty back?”36 Without the context of the first volume, Pat's question is perplexing; in fact, in Pat of Silver Bush, McGinty, Hilary’s treasured dog, is kidnapped by a robber, and Judy advises Hilary and Pat go visit a witch, “her” in the quotation, to successfully find the dog. The second case is when Pat asks, “Judy, don’t you remember that Hilary and I called the little hill by the Haunted Spring Happiness? We used to have such lovely times there.”37 Pat exploits the wording “used to” to indicate they shared happy times together in the past before this book, since at its beginning Hilary has already gone to Toronto. Finally, in section nine of the first chapter, the following exchange occurs between Judy and Pat:

“I s’pose his mother doesn’t be thinking inny more about him than she iver did?”

“I don’t know. He never mentions her name now. … And as for coming home … well, you know, since his uncle died and his aunt went to town he really has no home to come back to. Of course I’ve told him a dozen times he is to look upon Silver Bush as home. Do you remember how I used to set a light in this very window when I wanted him to come over?”

“And he niver failed to come, did he, Patsy?”38

This “light by the window as signal” instantly reminded me of Anne and Diana’s relationship in Anne of Green Gables, which indicated to me there should be a prequel describing their close childhood friendship. The characters talk about old memories that clearly occurred before Mistress Pat, so when reading these moments, I was very “chafed”—that is, irritated and impatient—to lack knowledge of what had happened before this story. That is when I jumped to Muraoka’s “Translator’s Afterword” and learned there was a prequel: “Even though I am publishing Pat Ojousan [MP] first before Gin no Mori no Pat [PSB], that is, publishing them in reverse order, I think you can find enough of the lively activities of ‘Judy’ and ‘Mistress Pat’ in this one book.”39 Though I had expected it, the existence of the prequel surprised me, and, understandably, I wondered why this reverse-order publication had happened because, so far, Muraoka had published her translations of Montgomery’s Anne series and Emily trilogy sequentially, following the heroines’ growth.40 She deliberately numbered the Anne series in subtitles in her paperbacks to ensure that her readers read the series according to protagonists’ growth, so it seemed to me that this uncharacteristic reverse publishing of the Pat books must be due to some special circumstances.41 However, as Muraoka did not reveal these circumstances, readers were left to deal with this unsolved mystery for a long time.

There is another notable point to discuss. In Muraoka’s “Afterword,” she writes that the readers will enjoy “the lively activities of ‘Judy’ and ‘Mistress Pat,’” but she never mentions Hilary—a very important character, who appears at the end and rescues Pat. In fact, Muraoka could not adequately discuss Hilary due to his absence in the sequel and the sequel’s insufficient information about him. It seems that Muraoka herself could not illustrate the character of Hilary based on just this novel. While it is sometimes said that the translator is the best reader of the work, since Muraoka did not have access to descriptions of Hilary and could not, therefore, understand him, it proves how essential the reading order is to fully grasp Hilary’s character and essential role in the Pat books.

For the near-orphan Hilary, Pat is like family; they have grown up together for ten years. As he matures, Hilary wants Pat to be more than a chum, but Pat wants to stay his friend. If one does not learn this in Pat of Silver Bush, it is hard to understand the significance of his absence through most of the novel of Mistress Pat and the magnitude of the reversal at the end of the novel, when Hilary comes for Pat at her lowest point, and Pat begins to live a new life with him. Unfortunately, the privilege of reading the books as intended was lost, chafing Japanese readers for a long time through the noticeable loss of context for the story.

In the 1980s, after learning of the prequel, I did not want to continue reading Mistress Pat. I thought, “Is that not like reading the ending of the mystery after skipping the middle?” At that time, the first volume was already published by a different publisher, so I gave up reading Mistress Pat in the middle and dashed to the bookstore to order the prequel. I wanted to read the Pat books from the beginning to fully understand the characters and background.

The Importance of Reading Pat of Silver Bush

As expected, after reading Pat of Silver Bush, I understood the characters better: from the beginning, Judy calls Pat “a queer child” because she “loved too hard,”42 so she fears loss and change, especially of her home and family. Because of her peculiarity, Pat has no close friends, and it is only after meeting Bets that she finds a bosom friend for the first time in her life. Their friendship is so rare and perfect that Bets’s sudden death from pneumonia brings Pat to complete despair: “When Bets had been dead for a week it seemed to Pat she had been dead for years, so long is pain. The days passed like ghosts. … Everything had ended. And everything had to begin anew. That was the worst of it. How was one to begin anew when the heart had gone out of life?”43 Pat suffers from the loss so intensely for such a long time that she cannot create new bonds with others, so she falls back into the old, the familiar: her home. She ultimately redirects her love from a person to her house: “Silver Bush was all her comfort now. Her love for it seemed the only solid thing under her feet. Insensibly she drew comfort and strength from its old, patient, familiar acres.”44 This is a pivotal moment. As Epperly points out, “the wrong turning that Pat took after Bets’ death in Pat of Silver Bush means that, as the years go by and everyone else changes and leaves, Pat holds on more and more desperately to the place Silver Bush, as though it alone can keep her safe and hold the beloved past close enough to touch.”45 The loss cannot be assuaged, even after many years, and she continues feeling very lonely. To understand why Pat turns her love from a person to attach herself so intensely to her home, it is essential to first read Bets’s death scene near the end of Pat of Silver Bush. In place of that lost friendship, in Mistress Pat, Pat even more devotes herself to her home, creating her own cozy world there and trying to keep it unchanged, which is the main feature of the work.46

Pat’s deep sense of loss echoes Montgomery’s own experience of losses, notably the death in January 1919 of her cousin and best friend, Frederica “Frede” Campbell MacFarlane, from pneumonia due to the second wave of the 1918 influenza pandemic (usually known in Montgomery’s time as the Spanish flu).47 Montgomery stayed by her deathbed until the end. She was enormously “grieved and worn out by Frederica’s death,”48 calling Frede “half my life.”49 She felt the urge to die along with her, a desire she expressed even many years later.50 Nevertheless, when she wrote about Frede’s death in her journal on 7 February 1919, thirteen days after her passing, Montgomery wrote of her determination to live for her two sons and to survive as a writer: “She died. And I live to write it!”51 Thirteen years later, at last, she directly used the real-life setting of Frede’s sombre death and recreated it in Bets’s beautiful and serene death scene in Pat of Silver Bush.

By reading Pat of Silver Bush first, readers can carefully comprehend another rare relationship between Pat and Hilary and understand more about the theme of loss in the Pat books. Pat and Hilary are depicted as perfect friends with a bond based on mutual understanding and shared tastes in houses and nature. Growing up, Hilary wants Pat as his girlfriend, but Pat refuses and wants to maintain their relationship as friends. After Bets dies, Pat has no friend but Hilary. In particular, reading the ending of Pat of Silver Bush clarifies how Hilary’s departure to Toronto means a huge loss to Pat: after their sad parting, “Pat stumbled up the path and across the field blindly and brought up against the garden gate. Then denied tears came. She simply couldn’t bear it. Everything gone! Who could bear it?”52 Here, “home” is irrevocably altered; her home is unrecognizable without Hilary. This might be intended to foreshadow that Hilary is more important than her home, but Pat does not notice it at the time. Instead, as the shock of his loss fades little by little, Pat gradually recognizes the beauty and consolation her dearest house always gives her. This loss of Hilary added to the loss of Bets leads to Pat’s over-attachment to her home: “It was such a loyal old house ... always faithful to those who loved it. You felt it was our friend as soon as you stepped into it. … Life could never be empty at Silver Bush.”53 Thus, it is only by reading the ending to the first volume that readers can clearly understand Pat and Hilary’s deep bond and how losing Hilary, in addition to Bets’s death, causes Pat to transfer her love to her home. Also, knowing how deeply Pat and Hilary are united is vital to the reader’s understanding of and emotional connection to Pat’s natural acceptance of Hilary’s proposal after his ten-year absence. Without reading the ending of the first novel, readers fail to recognize the severe losses Pat has borne prior to the sequel. These losses are the intended basis for understanding Mistress Pat; they enhance the tragedy of losing her beloved home and the joy of accepting Hilary’s marriage offer, making way for a new life and a new home.

There is another kind of painful loss of home for Pat in Mistress Pat. Pat’s rival, the vulgar May Binnie, starts to disturb the harmony and peace in the family when she enters Pat’s family as a bride by secretly marrying Pat’s elder brother Sid (a plot point which reflects Montgomery’s own experience with her son Chester’s secret marriage). Because of this, “Mistress Pat,” in fact, starts to lose hold of the old peacefulness and cosiness of her home. May’s marriage to the heir of Silver Bush reveals that Pat’s position as “mistress” of the house is a practical one, not a social one. The present social mistress is actually Pat’s mother, but, because she is not healthy, Pat acts as a surrogate for her and, in effect, runs the house. Pat enjoys being the main decision-maker regarding the home. May’s intrusion into the family threatens Pat’s status, illustrating the serious problem of the precariousness of an unmarried woman’s position in the family, which Montgomery herself suffered from before she married concerning the inheritance of her house from her grandfather. Although Pat’s father decides that May will become a mistress of a new house which will be built on another farm, Pat’s fear of loss of role is painful, and she must endure it and struggle to maintain her role for over five years; it is not (at least immediately) the physical loss of home, but the long, unsettling, unpleasant feeling of having one’s home usurped that is keenly felt by the readers who empathize with Pat’s point of view. In the end, Pat physically loses her home in a fire caused by May; it is only after losing this beloved place that Pat can transfer her affection for her home to the real, living person, Hilary.

After Judy dies and before Silver Bush burns, Montgomery’s description of Pat in depression (exactly reflecting Montgomery’s melancholy mood) is authentic and painfully invites the reader’s sympathy. On the night after Judy’s funeral, Pat cries out to her mother, “I’ve nothing but you and Silver Bush left now.”54 Montgomery’s superior description of Pat’s depression is genuine and touching; Pat now sometimes has “an attack of nerves.” She comes to love the evening “lonely walks by herself among the twilight shadows,” and she comes back from them looking “as if she were of the band of grey shadows herself. …”55

Pat’s depression after the fire is also poignant and real. Montgomery describes how, for Pat, “Life had suddenly become for her like a landscape on the moon. She had the odd feeling of not belonging to this or any world that has had felt once or twice after a bad attack of flu. Only … this feeling would never pass.”56 Further,

She [Pat] felt horribly old. Her love for Silver Bush had kept her young … and now it was gone. Nothing was left … there was only a dreadful, unbearable emptiness.

“Life has beaten me,” she told herself. She had had enough grief in her life to know that in time even the bitterest fades out into a not unpleasing dearness and sweetness of recollection. But this heart-break could never fade. Everything had fallen into ruins around her. She could never fit into the life at the Bay Shore. She had a terrible feeling that she did not belong anywhere … or to anybody … in this new sad lonely world.57

By this time, Pat’s correspondence with Hilary has ceased, so there is no recollection of Hilary in Pat’s mind, and she has no intention of relying on Hilary in any form. Moreover, she never considers marrying anyone. To her, at this stage, marriage is not included in her choices at all. Instead, she is thinking of working as a teacher, using an old licence, though the idea does not appeal to her.

The sudden appearance of Hilary at the end of Mistress Pat may seem abrupt, but for those who have already read Pat of Silver Bush and understand the profound bond between the characters, it is deeply satisfying to be convinced that the person the readers have been waiting for has finally appeared, and that Pat and Hilary’s story is settled.

The ending of Mistress Pat reveals how Pat and Hilary’s first encounter is important to understanding their strong bond. The moment Pat meets Hilary again at the ending of Mistress Pat, she recalls their first encounter:

Something seemed to have come with him … courage … hope … inspiration … that same dear sense of protection and understanding that had come to her that evening long ago when he had found her lost in the dark on the Base Line road. She held out both her hands but he caught her in his arms … his lips were seeking hers … a tremor half fear, half delight, shook her. And then that old, old, unacknowledged ache of loneliness she had tried to stifle with Silver Bush vanished forever. His lips were on hers … and she knew. It was like a tide turning home.58

This is evocation: eventually, the sense of protection and understanding that Pat felt when she first met Hilary, detailed in Pat of Silver Bush, returns to her after twenty-three years.59 This old memory parallels this ending scene wherein Hilary suddenly appears and holds her in his arms: his human touch restores the depressed, ghost-like Pat to a living person. Thus, the characters’ deep mutual understanding unites these two books. Without reading Pat of Silver Bush first, readers cannot understand how lonely Pat has been, or how essential Hilary has been to her.60 Hilary has built a new ideal house for her and asked her to breathe life into it. By obtaining this new house that she can cherish and pour her heart into and realizing her goal in life, Pat can start regenerating herself; she can share the dream of building up a new life with Hilary. The contrast of loss and new life is sharp at the ending of Mistress Pat.

Even for those who read both novels, the ending of Mistress Pat is so brief that the essential role played by the reconciliation might be overlooked. Caroline Jones states in her article “Montgomery’s Literary Explorations of Motherhood” that “Mistress Pat is a novel of loss,”61 and I concur with her statement. She further observes that “Jingle’s arrival and rescue of Pat are negligible and have only six pages in which to redeem six unhappy years.”62 Certainly, the section is short, but I do not think the events are insignificant; they ignite a new life for Pat. At the end of Mistress Pat, after Hilary suddenly reappears, being called back by Judy’s letter written on her deathbed, and Pat is revitalized, by being in his arms and being kissed—in other words, through physical contact. It is her body that wakes up first, and recognizes that the feeling she has long thought of as friendship is actually her true love for Hilary. A renewed energy and power spring up inside her, she escapes the depression caused by the loss of her beloved home and she starts to live again. “Pat stood quivering with his arms about her. Life was not over after all … it was only beginning.”63

Pat’s crucial moment of reunification can be compared to “resurrection,” as Pat herself describes her reunion with Hilary after his ten-year absence: “She always maintained [afterwards] she knew exactly what she would feel like on the resurrection morning.”64 Finally, at the end, when Hilary suddenly reappears and proposes to her, saying, “I’ve a home for you by another sea, Pat. And in it we’ll build up a new life,”65 this is certainly “resurrection” to Pat. By following this path, Pat will no longer have to see the ruins of her home, nor the new house that May will build on the site of Silver Bush. Liberated from her home and leaving the past behind, she will build a new life with Hilary by another sea.

Prior to the reunification, Pat has long been passive. Realizing that she loves Hilary and finding a new life with him changes her into an active person who can love spontaneously. After this transformation, her words become active, too: “I’ll go to the end of the world and back with you, Hilary,”66 she says, and, “I’d live in an igloo in Greenland if you were there.”67 As her words indicate, Pat is no longer dependent on Silver Bush: she is now released from her over-attachment to her home, and she gains the freedom and autonomy to go wherever she wants to go.

Montgomery depicts this moment of Pat’s transformation and regeneration vividly, but not all readers are satisfied with Mistress Pat’s ending. Epperly complains that Montgomery’s description is so brief that “The nightmare quality of Pat’s losses cannot be dispelled in the last-minute rescue.”68 This remark seems to prove that Epperly sympathized with Pat in the sequence of loss and saw the circumstances from Pat’s point of view. The reader’s disappointment seems mainly caused by Hilary’s “last-minute rescue” after his long absence from the sequel, which disregards the expectation set by the first volume’s foreshadowing of the reunion. Despite the brevity of Mistress Pat’s ending, the books do have a degree of symmetry: In Pat of Silver Bush, Pat consoles Hilary after his disillusionment at being reunited with his unloving mother and helps him find his life’s goal (to become an architect who can build an ideal house, a home just for Pat in which she cannot be usurped). Similarly, at the end of Mistress Pat, Hilary leads the despairing Pat to start a new life with him in Vancouver, in that perfect house. As Epperly points out in her analysis of the first book: “At the end of the second book ... Hilary will be there for her, as she is here for him, to transform disaster into hope.”69 Thus, Epperly acknowledges the symmetry between the two novels through the reversal of loss and hope, as she indicates that Hilary’s loss and regeneration with Pat in the first book foreshadows Pat’s loss and regeneration with Hilary at the ending of the second. Nevertheless, while Epperly indicates that the ending is too rushed to serve as an adequate denouncement, “resurrection” happens in a moment. Brevity is natural. It seems to me that briefness and the brilliance of the story’s ending have the effect of inviting the readers to reread and savour Pat’s striking and sudden change and regeneration. In fact, after reading both books, I reread the ending again and again to relish its impact and Pat’s “resurrection.” The powerful hope regenerated from Pat’s ending enabled me to exorcise the depressive mood in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although Pat’s house has burned down, her precious tradition and old affection are instilled in her new home, creating a kind of continuity. In the last scene of Mistress Pat, Hilary says to Pat, “we’ll build up a new life and the old will become just a treasury of dear and sacred memories … of things time cannot destroy.”70 So, the dear and beautiful memory of Silver Bush is shared together, unmarred by anyone. In their new life, only dear treasures such as the knocker of Silver Bush, Judy’s cream cow jug, Judy’s hooked rug, and Judy’s picture of white kittens are maintained and keep the fine tradition of Silver Bush.71 In writing this, Montgomery gives them both the hope of overcoming loss and of living a new life: that is, regeneration for Pat and Hilary.

Despite the above, Pat is not entirely dependent on Hilary for hope. Even if Hilary had not come to rescue Pat, she could have become a teacher. Besides, Pat has extraordinary abilities of her own: the ability to love people and things passionately and to make a comfortable home; she has strong household skills based on precious tradition. These abilities should not be underestimated.

As a whole, it seems that the reading of the Pat books is completely different depending on how much importance the reader finds in the ending and how much the reader accepts the author’s message of hope and regeneration. If, like Margaret Doody, one focuses on the “darker side” of the novel, it is true that in these two novels “Montgomery has incorporated some of her deepest and most dissonant insights into the nature of need and the assertions of power. She lets in the destructiveness that has played around the edges of all of her fiction.”72 Despite such darkness, I think the fact that Montgomery placed hope in this ending is essential and cannot be discounted. Readers encounter Pat’s ending with both surprise and relief. While it is possible for readers to dismiss the ending as convenient and improbable, accepting it as a satisfying denouement makes the difference in reading the Pat books.

Another reason not to discount the ending of Mistress Pat is its significance for its author. When Montgomery wrote Mistress Pat, she was depressed, and in the book she herself writes in defence of the happy ending: Uncle Horace says to Pat, “I don’t care a hoot for a book where they don’t get properly married … or hanged … at the last. These modern novels that leave everything unfinished annoy me.”73 Elizabeth Waterston states that this constitutes “a bit of self-congratulation for the real story-teller, who had been criticized for the too-sunny pictures of life in her fiction.”74 While I agree with Waterston’s opinion, we live and breathe reality every day, and the act of reading a book is, at least for some people, to escape from real life for a while, to experience a happier time, to be comforted and healed, and to be given the energy and courage to face reality again. This is the reason I love to read Montgomery’s books, for their healing and energy, and I suspect most of her readers do so for similar reasons. Those interested in a “real” story about Pat, for example, living the rest of her life like a ghost, “drifting from one place to another ... rootless,” living in houses she hates, would not look to Montgomery.75 Their brightness is why Montgomery’s books are still so popular with readers across time and place, because her books give us the therapeutic comfort and energy we need to live through predicaments.

While Montgomery made Pat’s ending happy to meet the expectations of her readers, this may not be the full reason for her literary choice: she herself seems to have needed to craft a happy ending in her anguished life during the 1930s, when she was on the verge of losing her beloved manse due to her husband Ewan’s worsening depression, tied to the understanding of predestination in Calvinist theory. Already on 5 November 1934, before she wrote the ending of Mistress Pat, she worried about leaving the manse: “The thought of leaving Norval hurts me horribly. I love it so … And go—where? To Toronto I suppose, to live in some dreary cramped house on a street where scores of exactly similar houses stand cheek by jowl. The thought is intolerable.”76 This fear of the loss of her dearest manse closely reflects Pat’s fear of loss and change: Pat’s sense of loss echoes Montgomery’s own loss and her attachment to home. In this respect, they are one. Montgomery acknowledges this overlap when she writes, “Not externally but spiritually, she is ‘I.’”77

When she finished the last chapter of Mistress Pat on 30 November 1934, Montgomery wrote, “I got the last chapter of Pat II done. Such a relief! I thought so many times this fall I should never get it done. I never wrote a book in such agony of mind before …” She continues, “My loneliness was awful. I had a bad neurasthenic spell at 8 but feel better now.”78 Indeed, when Ewan resigned his position as a minister on 13 February 1935, an action that meant they would have to leave the manse, she again wrote of how she loved the beauty of nature and the manse in Norval and had had “sometimes dreamed of buying a certain very beautiful river lot not far from the manse, building a nice home on it and spending the rest of our days there, helping the church and the community.”79 This dream of hers strongly reflects Pat’s revival at the end of Mistress Pat. After Montgomery started to search for a new house, her dream of regeneration came true. She found what would become her favourite house in Toronto, she sold her shareholdings to buy it so she could bring her sons and enjoy the social life in the city with her family. She writes in her journal on 15 March 1935: “I do want a nice home to end my days in—‘Journey’s End’ I am going to call it.”80 Montgomery moved from a manse by the Credit River to live in her new house by the Humber River, in the city of Swansea, in other words, “by another sea,” and build up a new life for herself with her own money, earned by her pen. Though Montgomery’s health was failing and her days were difficult in the last years of her life, when she wrote Mistress Pat in Norval, it seems she was trying to recover from her distressing situation and parallel Pat’s new life with her own wish for recovery. The Pat books may echo her wish for her own regeneration.

Despite happy endings being intrinsic to her work, Montgomery does not make Pat’s ending a simple fairy tale of “happily ever after.” This can be seen in the last sentence of Mistress Pat: “The old graveyard heard the most charming sound in the world … the low yielding laugh of a girl held prisoner by her lover.”81 She sneaks in a metaphor equating marriage with a graveyard—suggesting death—and with a prison at the very end. Montgomery implies that marriage is not a promise of perfect happiness, but that to marry is in a sense to yield to a new chain, a bondage, a prison. Pat is liberated from the restraints of her home, but she also leaves the warm, woman-centred world of Silver Bush and enters a new prison with her husband. She may become yielding or submissive to her husband in their future home. Thus, despite the happy nature of the ending, Montgomery also includes darker aspects of the realities of life.

I call the ending of Mistress Pat a “happy” ending not because Pat lands in the official, legal, and religious institution of “marriage,” but because Pat realizes her true love for Hilary and experiences the rapture of being loved by someone she loves: that is happiness. “Building up a new life” with that person can be called a “happy” ending. In Pat’s story, Montgomery may have been expressing her wish for happiness to come in the end.

Ultimately, looking back to the original problem, Pat’s insecure position and attachment to her house originate in the entailment that only sons can inherit homes and land. Pat is well aware of this convention by the time she is eighteen years old at the latest, and it is knowledge she demonstrates when she discloses her stance to Hilary when he leaves for Toronto at the ending of Pat of Silver Bush: “you’re to build a house for me some day. I’ll live in it when Sid gets married and turns me out of Silver Bush. And you’ll come to see me in it … I’ll be a nice old lady with silver hair… and I’ll give you a cup of tea out of Grandmother Selby’s pot … and we’ll talk over our lives... .”82 At this point, Pat already recognizes the irrationality of the patriarchal order of succession, revealing that she does not live in a fantasy world entirely, and this recognition, indicated at the end of this first volume, should be the basis of understanding of Pat’s deepening fear of loss of her home in the second book. As Catriona Sandilands uncovers, Pat’s insecurity stems from “heteropatriarchy, in which men and not women are tied to the land and in which marriage and not lifelong attentiveness is the relation that ultimately counts in terms of belonging.”83 This ideology emphasizes Pat’s unstable position. I agree with Sandilands’s further statement: in the Pat novels, Montgomery consistently complains about “the limited options available for women who might choose not to marry or who might choose vocation or, in this case, location, over heterosexual coupling.” Then she concludes, “Pat’s love of the place is only pathological, on this reading, if one considers heteronormativity a ‘natural’ organization of space and life and opposite-sex romance the only love that really matters.”84 While it seems perfectly acceptable for girls like Jo and Beth in Little Women to stay unmarried in their happy home, and to live for the family they love, it is also only natural that a girl like Pat, who has been blessed with a happy home since birth, would want her happiness to last as long as she lives and that she would not want to change nor leave her home. Pat’s affection for her home may be too strong, but it is not likely to be pathological compulsion.

Certainly, readers who start with Mistress Pat might be surprised by Hilary’s abrupt appearance and Pat’s sudden change leading to their happy ending. Although I do not reject happenstance reading or deny its potential, in this case, without reading the first book, and because of the brevity and scarce explanation at the ending of the second book, readers have difficulty fully grasping the brilliant reversal and may not understand why Hilary is the only person for Pat.

Reading Out of Order in Japan

In 2020, I conducted experiments focused on reading the Pat books out of order to gather vicarious experiences from contemporary readers and learn how they felt about the novels. I asked two acquaintances who had never read the Pat books before to read Mistress Pat followed by Pat of Silver Bush in translation, and to share their reflections.

The first reader, Eri,85 who had never read any of Montgomery’s books, told me that she enjoyed the sequel alone but that she could understand neither what kind of person Hilary was nor how deeply he loved Pat until the book’s end. Further, Eri could not understand the special nature of the characters’ relationship and its history; they are described as “old friends,” but how old they were when they got to know each other and how long they had been close friends remained unclear to her, as they were not detailed in the second book.86 Hence, Eri did not comprehend how deeply Hilary had affected Pat’s character formation when Pat was a girl, and how closely they were united. As a result, she was rather surprised to know how deeply Hilary continues to love Pat during and after his ten-year absence. Another reader, Misako, who loves the Anne series but had never read other Montgomery books, told me that she enjoyed reading Mistress Pat, but she could not empathize with Pat because, whereas Anne acquires everything from her orphanhood, Pat has everything from birth. Misako could not understand why Pat attached herself so intensely to her home.

For both readers, after reading Pat of Silver Bush, the frustration and dissatisfaction they felt were to some degree addressed, and they understood the author’s intentions. Notably, through reading the first novel, Eri discovered what a huge loss Bets’s death is to Pat. By understanding the source of Pat’s deep loss, Eri could better recognize how Pat’s reunion with Hilary signifies her regeneration. She related that after finishing the second volume alone, she had not been completely convinced of Pat and Hilary’s happy engagement. Eri had been plagued with the question of why they are happy, which made her yearn to know more about the first book. Consequently, she really enjoyed reading the first volume, which solved the puzzle. Pat shares Hilary’s trauma and is deeply involved in the making of Hilary as a man. On reading Pat of Silver Bush, Eri finally understood that it is because of their intense and cumulative eleven years together that they can get engaged without feeling uncomfortable at the end, even though they have been apart for thirteen years. Similarly, Misako said that by reading the first volume, she could finally understand the deep relationship between Pat and Hilary. Misako related that if she had read the second book alone, she would not have been able to empathize with Pat’s feelings. Although she knew the ending of the second volume, for Misako, reading the first book was a series of discoveries, of puzzles to be solved.

Considering their overall impressions of reading in reverse order, which is the ultimate point of this work, the unsatisfactory nature of Eri and Misako’s initial reading experience remained with them; their out-of-order reading left them dissatisfied and feeling a sense of loss for their failure to obtain the complete picture as the author intended. They were saddened by the lost opportunity to grow up with the heroine.

Unlike today’s readers, those of previous generations could not control their reading order. The translator who published the translations of Montgomery’s The Blue Castle and A Tangled Web, Yumiko Taniguchi, is a reader from this older generation. In an interview on 7 May 2018, she told me that although she enjoyed Mistress Pat in its own way, she could not understand the book clearly; she could not grasp what kind of person Hilary was, and she found it difficult to fathom the relationship between Hilary and Pat because of his absence through most of Mistress Pat. Although Taniguchi had read the abridged version of the prequel, The Girl of Silver Birch House, this version is shortened for children and only traces the main plot, so she was left feeling unsatisfied and could not fully enjoy the story. After 1981, she read the complete version, but, unfortunately, her discontent persisted because of wording inconsistencies in these translations. This frustration motivated Taniguchi to produce a new set of translations in the twenty-first century.

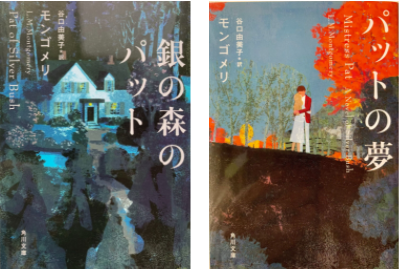

Right: Book cover of Pat no Yume [Pat’s Dream (Taniguchi’s title of Mistress Pat)]. Japanese translation by Yumiko Taniguchi. 2012. Cover illustration by Tatsuro Kiuchi. Image courtesy of Kadokawa Bunko.

In 2012, Taniguchi published new and complete translations of Pat of Silver Bush and Mistress Pat. In the works’ respective “Translator’s Afterwords,” she discloses her frustration. In Pat of Silver Bush, she explains that “the second volume was published before the first volume, so the readers at that time felt a little uncomfortable and confused. This is because the second volume was written on the premise that the readers had already read the first and begins when Pat is already twenty years old. So, I wholeheartedly recommend that you all read this book first, and the second after this book to ‘feel satisfied.’”87 In the second volume, she writes: “Thank you very much for waiting. Finally, this second volume is published. If you have not read the first volume yet, please read Pat of Silver Bush first before reading this book. You can immerse yourself into the story far more smoothly and comfortably …”88 She further elaborates: “By publishing the Pat books out of order, the storyline was reversed so that the readers in those days had difficulty understanding the contents of the story. This is why I published the new translation, to ensure that the readers can read the Pat books in order. ...”89 Taniguchi’s uneasiness with the disordered reading resulted in her producing fresh, lively translations, giving new life to Japanese readers.

Why Order Matters

Due to the original being unavailable, Japanese readers could not read the complete translation of Pat of Silver Bush until 1981, which is a great loss. This circumstance of translation left at least one generation of Japanese readers encountering the Pat books in reverse sequence, depriving them of the opportunity to read the books in the intended order. For that generation, if one had read the sequel at twenty years of age, one would have been able to finally read the prequel only at the age of forty. The lack of the prequel’s availability robbed the young reader of the chance to grow up together with Pat. This failure also has long-lasting effects: Anemu, who described her reverse reading experience as one of her biggest regrets in life, in 2016 commented to another Montgomery reader that “I’m very jealous that you can read along with the flow of time” by reading the Pat books in order.90

From my study, it becomes apparent that when reading the Pat books in reverse order, one cannot fully understand the drama of Pat and Hilary’s loss and new life. It also emerges that the Pat books encapsulate Montgomery’s own loss of her best friend and her wish for regeneration in her personally difficult times in the 1930s. When they read the Pat books in order, book lovers get to enjoy the process of the heroine’s coming of age and to share experiences alongside her. The contrast between Pat’s loss of her best friends in Pat of Silver Bush and her regeneration at the end of Mistress Pat is so vivid that it leaves a strikingly emotional impact on readers. Becoming acquainted with the Pat books in order enables readers to experience the full effect of the works, to move with Pat through the carefully choreographed events as intended, and to live with her through the shock and pain of loss and the sweet surprise of gain.

Setting aside the limitations stemming from reading the Pat books out of order, I will now consider the broader significance of reading Montgomery’s books. Almost all of her novels allow her readers the pleasure of “growing up together” with the heroines by absorbing themselves into the worlds she creates: they are Bildungsromane. A happy ending is one of the characteristics of Montgomery’s work, becoming even more effective when great loss and emptiness precede it: for instance, the loss of Anne’s first baby, Joy, enhances Anne’s happiness over the birth of Jem, and the loss of Walter increases the joy of Rilla’s reunion with Kenneth after war. For Montgomery readers, merely knowing how each story ends is not enough: readers want to journey through life events with the heroines, laughing, crying, and sharing with them, and Montgomery enables her readers to relish to full effect the suspense and romance her characters experience. Not only does savouring Montgomery’s created worlds allow escape from the difficulties of daily life, but the perseverance of her characters and the way they work through the challenges life throws at them encourage the readers to face and live through life’s hard realities with renewed and fresh energy. Montgomery writes about the pain of loss in her novels, such as the loss of her best friend Frede, and she gains the strength to live on by writing out her grief, transforming it into beautiful fiction, creating a new life out of loss, and finishing it with a happy ending. Her novels provide the therapeutic energy necessary to live through unpredictable times; this is true for her characters such as Pat, for her readers, and for herself.

The Pat books are stories of loss as well as stories of “building up a new life,” self-recognition, and the celebration of women’s power to make a home. The novels reflect Montgomery’s own life experience from her mature perspective, making Pat a very different character from her other heroines. While she gave Anne imagination and Emily talent, Montgomery gave Pat herself, who can love deeply. As much as a love story, it is about the possibility of Pat being able to make and love a home but in a less grief-stricken way than she does with Silver Bush. By showing how the agony of loss is ultimately followed by the unexpected joy of a new beginning, Montgomery provides encouragement and inspiration. The Pat books give us hope that loss will give way to gain, and that emptiness will be followed by fulfilment. In the end, although the reading order might not completely obscure Montgomery’s intentions for Pat, as this work has shown, it undeniably affects the readers’ understanding of Pat and her long emotional journey through life.

About the Author: Kazuko Sakuma teaches English language and literature at Sophia University in Tokyo, Japan, where she completed her M.A. and Ph.D. She has presented and published extensively on nineteenth- and twentieth-century women writers including Willa Cather and L.M. Montgomery. Her primary research interests are gender, war and peace, and translation. She has contributed a chapter on Anne of Green Gables in Japan to Reflections on Our Relationships with Anne of Green Gables: Kindred Spirits (2021), and a chapter on the gendered representation of the white feather in L.M. Montgomery and Gender (in progress).

Banner image derived from (Left to Right): Book cover of Pat no Yume [Pat’s Dream (Taniguchi’s title of Mistress Pat)]. Japanese translation by Yumiko Taniguchi. 2012. Cover illustration by Tatsuro Kiuchi. Image courtesy of Kadokawa Bunko. Book cover of Pat Ojousan [Mistress Pat]. 1965. Japanese translation by Hanako Muraoka. Cover illustration by Yoshimasa Murakami. Image courtesy of Shincho Bunko. Book cover of Mistress Pat. 1935. Ryrie-Campbell Collection, KindredSpaces.ca, 549 MP-MS-1ST. Book cover of Pat of Silver Bush. 1933. Ryrie-Campbell Collection, KindredSpaces.ca, 548 PSB-MS-1ST. Book cover of Gin no Mori no Pat (jo) [Pat of Silver Bush 1]. 1980. Japanese translation by Tokiko Tanaka. Cover illustration by Sachiko Yamanaka. Shinozaki Shorin. Book cover of Gin no Mori no Pat (ge) [Pat of Silver Bush 2]. 1981. Japanese translation by Tokiko Tanaka. Cover illustration by Sachiko Yamanaka. Shinozaki Shorin. Book cover of Gin no Mori no Pat [Pat of Silver Bush]. 2012. Japanese translation by Yumiko Taniguchi. Cover illustration by Tatsuro Kiuchi. Image courtesy of Kadokawa Bunko.

- 1 Rubio, Lucy Maud Montgomery 426. The original letter is housed at the University of Guelph Library, The L.M. Montgomery Collection.

- 2 Epperly, Fragrance 211–27.

- 3 Lefebvre, Books 525–27.

- 4 MacDonald, “Reflections” 155.

- 5 Rubio 418.

- 6 Fishbane, “My Pen” 132.

- 7 Cavert, “To the Memory” 50.

- 8 Montgomery, SJ 4 (1 Aug. 1933): 227.

- 9 “Loss,” def. 2, a, b, c, e; “Regeneration,” def. 1.a; and “Resurrection,” def. 1.b, 3.

- 10 Montgomery, MP 272, 273.

- 11 Montgomery, SJ 4 (15 Jan. 1934): 252.

- 12 Montgomery, SJ 4 (21 May 1934): 265.

- 13 Taniguchi made the same observation as I do in her “Translator’s Afterword” in Gin no Mori no Pat, 572.

- 14 Like Anne of Green Gables, Pat of Silver Bush has thirty-nine chapters with a name for each chapter, such as “Introducing Pat” for the first chapter, while Mistress Pat has eleven chapters titled according to year, such as “The Second Year” as Chapter 2. Further, the lengths of the chapters are not consistent. In addition, the publishing companies for British editions are different: Pat of Silver Bush was published by Hodder Stoughton, Montgomery’s British publishers since Rilla of Ingleside (1921), but they refused to publish Mistress Pat, giving no reason. Instead, Harrap’s, who handled a lot of the preprints of Montgomery’s books, published Mistress Pat, and the book “appeared among the ‘best selling’ books in England” in December 1935. See Montgomery, SJ 4 (15 Mar. 1935): 360, 394; SJ 5 (16 May 1935): 13; SJ 5 (27 Dec. 1935): 51, 352–53, 354.

- 15 See Muraoka, Hanako. This translation of Mistress Pat was titled Pat Ojousan in Japanese.

- 16 This abridged translation was titled Shirakaba Yashiki no Shoujo [A Girl of White Birch House], translated by Tokiko Tanaka. See Tanaka, Tokiko, Shirakaba, “Translator's Afterword.” It is notable that Tanaka purposefully omitted “Pat” from her interpretation of the book’s title.

- 17 Tokiko Tanaka completed this translation as well. See Tanaka, Tokiko, Gin no Mori no Pat (ge) [Pat of Silver Bush 2], “Translator’s Afterword.”

- 18 Anemu, “L.M. Montgomery” (my translation).

- 19 Hanako Muraoka translated the Anne books sequentially except Rainbow Valley, which was published on 30 June 1958 after Anne’s House of Dream on 20 May 1958 and before Anne of Ingleside on 5 October 1958.

- 20 Tanaka, Mihoko, Aspects 96–99.

- 21 Tokiko Tanaka deleted Chapters 13, 14, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 33, and 34 and shortened the remaining chapters.

- 22 Tanaka, Tokiko, Shirakaba, “Translator’s Afterword” 243 (my translation).

- 23 Taniguchi, Gin no Mori, “Translator’s Afterword” 572.

- 24 Tanaka, Tokiko, Gin no Mori (ge), “Translator’s Afterword” 242–43 (my translation).

- 25 Only recently, in 2014 when the biography of Hanako Muraoka was written and published by her granddaughter Eri Muraoka as An no Yurikago: Muraoka Hanako no Shougai [Anne’s Cradle: The Life and Works of Hanako Muraoka, Japanese Translator of Anne of Green Gables] did most Japanese readers discover that Muraoka had belatedly obtained her copy of Pat of Silver Bush and had begun translating it on 20 October 1968. Five days after she started her translation, she suddenly passed away due to cerebral thrombosis. Her manuscripts are housed in Toyo Eiwa Jogakuin Archives, The Muraoka Hanako Collection.

- 26 Mackey, “Reading.”

- 27 Mackey.

- 28 Mackey.

- 29 Mackey. In her article “‘Anne Repeated’: Taking Anne Out of Order,” Laura Robinson performs a reading of the Anne series out of order—in the order in which the books were written. She sees the three later novels as Gothic self-parodies, and finds out that they undermine the idealized picture of the happy Blythe family of the previous books.

- 30 Iser, Implied Reader 294.

- 31 Mackey.

- 32 Mackey.

- 33 Mackey.

- 34 Montgomery, MP 3–4.

- 35 Montgomery, MP 10.

- 36 Montgomery, MP 10.

- 37 Montgomery, MP 14.

- 38 Montgomery, MP 57.

- 39 Muraoka, Hanako, “Translator’s Afterword” 496–97 (my translation).

- 40 Muraoka published her translations of Montgomery’s Anne series and the Emily trilogy in order, based on the heroines’ growth, except Rainbow Valley, which came out just about three months before Anne of Ingleside (both in the same year, 1958).

- 41 For example, Hanako Muraoka numbered Rilla of Ingleside as Dai Juu Akage no An [The Tenth Anne of Green Gables], following the protagonists’ growth.

- 42 Montgomery, PSB 2. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “queer,” adj. (1) has the definition of 1.a.: “Strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric.” It is the Irish housemaid, Judy, who calls Pat “a queer child,” so I suppose the definition of “queer fellow,” def. (a) “chiefly Irish English and Nautical, an odd or eccentric person, a ‘character,’” is the closest we can approximate to the meaning of the word Montgomery used.

- 43 Montgomery, PSB 230.

- 44 Montgomery, PSB 231.

- 45 Epperly 218.

- 46 Margaret Doody discusses Montgomery’s darker side, reading Mistress Pat as “a story dealing with obsession” (“L.M. Montgomery” 47).

- 47 Montgomery, SJ 2 (7 Feb. 1919): 287.

- 48 Rubio 208.

- 49 Montgomery, SJ 2 (7 Feb. 1919): 295.

- 50 Montgomery, SJ 4 (25 Jan. 1934): 253.

- 51 Montgomery, SJ 2 (7 Feb. 1919): 295.

- 52 Montgomery, PSB 277.

- 53 Montgomery, PSB 277–78.

- 54 Montgomery, MP 265.

- 55 Montgomery, MP 267–68.

- 56 Montgomery, MP 270; ellipses in original.

- 57 Montgomery, MP 271; ellipses in original.

- 58 Montgomery, MP 272–73; ellipses in original.

- 59 Montgomery, PSB 65–66.

- 60 For the importance of reading the first encounter of the main characters, see Mackey.

- 61 Jones, “New Mother” 105.

- 62 Jones 105.

- 63 Montgomery, MP 273; ellipses in original.

- 64 Montgomery, MP 235.

- 65 Montgomery, MP 273.

- 66 Montgomery, MP 273.

- 67 Montgomery, MP 274.

- 68 Epperly 219–20.

- 69 Epperly 217.

- 70 Montgomery, MP 273; ellipses in original.

- 71 Note that there is no mention of Pat’s mother Mary Gardiner at the ending.

- 72 Doody 47.

- 73 Montgomery, MP 134; ellipses in original.

- 74 Waterston, Magic Island 182.

- 75 Montgomery, MP 272; ellipses in original.

- 76 Montgomery, SJ 4 (5 Nov. 1934): 315.

- 77 Rubio, Lucy Maud Montgomery 426.

- 78 Montgomery, SJ 4 (30 Nov. 1934): 327.

- 79 Montgomery, SJ 4 (13 Feb. 1935): 344.

- 80 Montgomery, SJ 4 (15 Mar. 1935): 360.

- 81 Montgomery, MP 277; ellipses in original.

- 82 Montgomery, PSB 276; ellipses in original.

- 83 Sandilands, “Fire, Fantasy, and Futurity” 40.

- 84 Sandilands 38.

- 85 Readers’ names have been changed for the sake of anonymity.

- 86 Pat was eight and Hilary was ten years old when they first met, and they were close friends for ten years until he left PEI in Mistress Pat.

- 87 Taniguchi, Gin no Mori no Pat, “Translator’s Afterword” 572 (my translation).

- 88 Taniguchi, Pat no Yume, “Translator’s Afterword” 552 (my translation).

- 89 Taniguchi, Pat no Yume, “Translator’s Afterword” 557 (my translation).

- 90 Anemu (my translation).

Works Cited

Anemu. “L.M. Montgomery, Gin no Mori no Pat, Pat Ojousan.” [L.M. Montgomery, Pat of Silver Bush, Mistress Pat.] Yuugata Nikki [Evening Journal]. https://ameblo.jp/anem/entry-10709818274.html.

Bode, Rita, and Lesley D. Clement, editors. L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2015.

Bode, Rita, and Jean Mitchell, editors. L.M. Montgomery and the Matter of Nature(s). McGill-Queen’s UP, 2018.

Cavert, Mary Beth. “‘To the Memory Of’: Leaskdale and Loss in the Great War.” Bode and Clement, pp. 35–53.

Doody, Margaret. “L.M. Montgomery: The Darker Side.” Mitchell, pp. 25–49.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance. U of Toronto P, 1992.

Fishbane, Melanie J. “‘My Pen Shall Heal, Not Hurt’: Writing as Therapy in Rilla of Ingleside and The Blythes Are Quoted.” Bode and Clement, pp. 131–44.

Iser, Wolfgang. The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett. Johns Hopkins UP, 1974.

Jones, Caroline E. “The New Mother at Home: Montgomery’s Literary Explorations of Motherhood.” Bode and Clement, pp. 91–109.

Lefebvre, Benjamin. Books by L.M. Montgomery. The Blythes Are Quoted by L.M. Montgomery, Penguin Canada, 2009, pp. 525–27.

“Loss, N.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, 2021,

https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/110406?rskey=1UB4HB&result=1&isAdvanced=…. Accessed 15 May 2021.

MacDonald, Heidi. “Reflections of the Great Depression in L.M. Montgomery’s Life and her Pat Books.” Mitchell, pp. 142–58.

Mackey, Margaret. “Reading In and Out of Order: Living In and Around an Extended Fiction.” Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies. https://journaloflmmontgomerystudies.ca/jlmms/2/1/reading-and-out-order-living-and-around-extended-fiction.

Mitchell, Jean, editor. Storm and Dissonance: L.M. Montgomery and Conflict, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008.

Montgomery, L.M. The Blythes Are Quoted. Edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, Penguin Canada, 2009.

---. Mistress Pat. 1935. Seal Books (McClelland-Bantam), 1988.

---. Pat of Silver Bush. 1933. Seal Books (McClelland-Bantam), 1988.

---. Rilla of Ingleside. Edited by Benjamin Lefebvre and Andrea McKenzie. 1921. Penguin Canada, 2010.

---. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1985–2004. 5 vols.

Muraoka, Eri. An no Yurikago: Muraoka Hanako no Shougai [Anne’s Cradle: Life and Works of Hanako Muraoka, Translator of Anne of Green Gables]. 2008. Shinchosha, 2011.

Muraoka, Hanako. “Translator’s Afterword.” Pat Ojousan [Mistress Pat], by L.M. Montgomery, translated by Hanako Muraoka, Shinchosha, 1965, pp. 494–97.

“Queer, Adj. (1).” Oxford Dictionary, Oxford UP, 2021, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/156236?rskey=nbYr0o&result=2&isAdvanced=false#e id.

“Regeneration.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, 2021, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/161223?redirectedFrom=regeneration#eid.

“Resurrection, N.” Oxford Dictionary, Oxford UP, 2021, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/164104?rskey=3Uvrwk&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid.

Robinson, M. Laura. “‘Anne Repeated’: Taking Anne Out of Order.” Seriality and Texts for Young People: The Compulsion to Repeat, edited by Mavis Reimer, Nyala Ali, Deanna England, and Melanie Dennis Unrau, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, pp. 57–73.

Rubio, Mary Henley. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Anchor Canada, 2008.

Sandilands, Catriona. “Fire, Fantasy, and Futurity: Queer Ecology Visits Silver Bush.” Bode and Mitchell, pp. 27–41.

Tanaka, Mihoko. Aspects of the Translation and Reception of British Children’s Fantasy Literature in Postwar Japan: With Special Emphasis on The Borrowers and Tom’s Midnight Garden. The Academic Society of Tokyo Woman’s Christian University, 2009.

Tanaka, Tokiko. “Translator’s Afterword.” Gin no Mori no Pat (ge) [Pat of Silver Bush sequel], by L.M. Montgomery, translated by Tokiko Tanaka, Shinozaki Shorin, 1980–81, pp. 239–44.

---. “Translator’s Afterword.” Shirakaba Yashiki no Shoujo [A Girl of White Birch House (Tanaka’s title of Pat of Silver Bush)], by L.M. Montgomery, translated by Tokiko Tanaka, Junior Best Novels 13, Iwasaki Shoten, 1974, pp. 242–43.

Taniguchi, Yumiko. “Translator’s Afterword.” Gin no Mori no Pat [Pat of Silver Bush], by L.M. Montgomery, translated by Taniguchi, KADOKAWA, 2012, pp. 569–73.

---. “Translator’s Afterword.” Pat no Yume [Pat’s Dream (Taniguchi’s title of Mistress Pat)], by L.M. Montgomery, translated by Taniguchi, KADOKAWA, 2012, pp. 552–57.

Waterston, Elizabeth. Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery. Oxford UP, 2008.

Article Info

Copyright: Kazuko Sakuma, 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.

Copyright: Kazuko Sakuma, 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.