This story narrates through the eyes of a cat how mental health relates to prayer and nature by exploring the redemption of Sara Ray, a nervous, miserable, and undeveloped character in L.M. Montgomery’s The Story Girl and The Golden Road.

I was at the Pulpit Stone when I was caught in Sara Ray. Her storm of sentiment clouds over you when you’re in a sunny place yourself, downing you as suddenly as lightning. I think I was punished for greed. That morning, I had dipped my lucky whiskers in two saucers of cream. Later, I had followed the Story Girl into the granary, where a mouse also found its way to my belly. I think I should have spared the mouse. For some other day. Afterwards, I was indisposed to everything but sleep.

If not for the solitude, I wouldn’t have napped in the King orchard. Barn cats—common, feral creatures—were lounging in the granary, and the swallows were creating a deplorable din in the hayloft. I refused to sleep at Aunt Janet’s; she uses undignified implements like brooms and sticks in my presence. There was too much bustle at Aunt Olivia’s. You would expect the King children to spend the last day of June outdoors, but this year they were embroiled in a silly rivalry over the library fund. Even as I sauntered toward the orchard, I could hear the King crew trip over each other to earn an extra quarter. The Story Girl was washing dishes, trying to scrape the highest contribution before handing it all to her teacher the next day.

When I woke up, the sun had begun its gradual descent behind the pines. The late apple tree was flaunting a lavish bloom and letting the breeze pluck some of its sweetest blossoms. A quivering shadow shuffled along the sward. I did not take much notice, imagining it to be the ghost of Emily King. I would have run for my life if I had known it was Sara Ray.

“Oh, oh Paddy! It’s you, it’s you.”

Friends call me Pat or Paddy. Others, including Sara Ray, should call me Patrick Grayfur, Esq. Though I heroically resisted Sara’s strokes and cuddles, her cold, thin fingers managed to dishevel my carefully washed, silvery-grey hair, turning the dark stripes on my back into a jumbled mess. When she stubbed my wee black nose with her elbow, I bravely restrained my big black paws from taking revenge. Through much practice, all of us had learned to keep our temper, disgust, and irritation in check when we were with Sara Ray. She always meant well, but her actions never reflected her intentions. The interludes between her crying spells were short and few, and none of us liked to upset her nerves, even for play. Just then, she was looking paler than usual.

“I know that you cannot tell this to a soul, so I’ll tell you, Paddy. Ma does not know that I am here. You know how she likes me home well before sunset. But I said to her that I wanted to discuss my lessons with Cecily. She said that I could send a message with Judy Pineau, but I insisted. I said I won’t understand the lesson that way. Don’t you think it was awfully clever of me?”

She cupped my face in her hands and smiled into my eyes. Her small, white teeth nearly apologized for making her look pretty, even as a dimple peeked shyly.

“But she said that I will have to read seven chapters of the Bible when I’m back. Because I didn’t complete my lessons earlier. And that is a pity, Paddy, because I have come here to pray. I didn’t tell her though. She would have told me to pray at home. I have been terribly restless today, you know. I didn’t even want to meet Cecily. I just wanted to be on my own. But when I was climbing up the hill, I felt horrible and lonely.”

She choked on a sob, and her monologue continued with sighs and hiccoughs.

“So, I thought I would meet Cecily, after all. Perhaps the Story Girl would cheer me with a story. I do love her stories, Paddy. But ma does not like her one jot. Even when I left today, she said, ‘Don’t let that Sara Stanley distract you.’ I feel like crying when ma tells me to stay away from the Story Girl. I do like her so. Everybody likes her. Sometimes I feel like crying because everybody likes her.”

It can’t be easy sharing names with the Story Girl. Big shoes to fill, and, mind you, the Story Girl has exquisite feet. In fact, the name “Sara Stanley” can never express the allure of that silver-tongued raconteuse. That’s why she prefers calling herself the Story Girl. The rest of us prefer it too, partly so that we don’t confuse her with Sara Ray. Not that such confusion could ever arise. I confess that even as Sara Ray kissed me between the ears, I was lost in thoughts of the Story Girl. The Story Girl’s fist boxed my ears, even as her voice glided over me, praising my exceptional skill in catching rats.

“You are a dear, sweet cat, Paddy. I’ll just stay here now. I feel I can brave the sunset now that you’re with me. I didn’t really want to meet anyone, but I didn’t want to be all alone either. Oh, please don’t go anywhere, okay?”

Sara Ray’s compliment deflated any optimism that I had felt that day. I can digest copious amounts of flattery, but “sweet cat”? I missed the Story Girl then; she would have called me an “old rascal.” Only she could honey words to feline standards. As Sara leaned into the Pulpit Stone beneath me, I wanted to jump over her head and make my great escape. But I didn’t; think what you may.

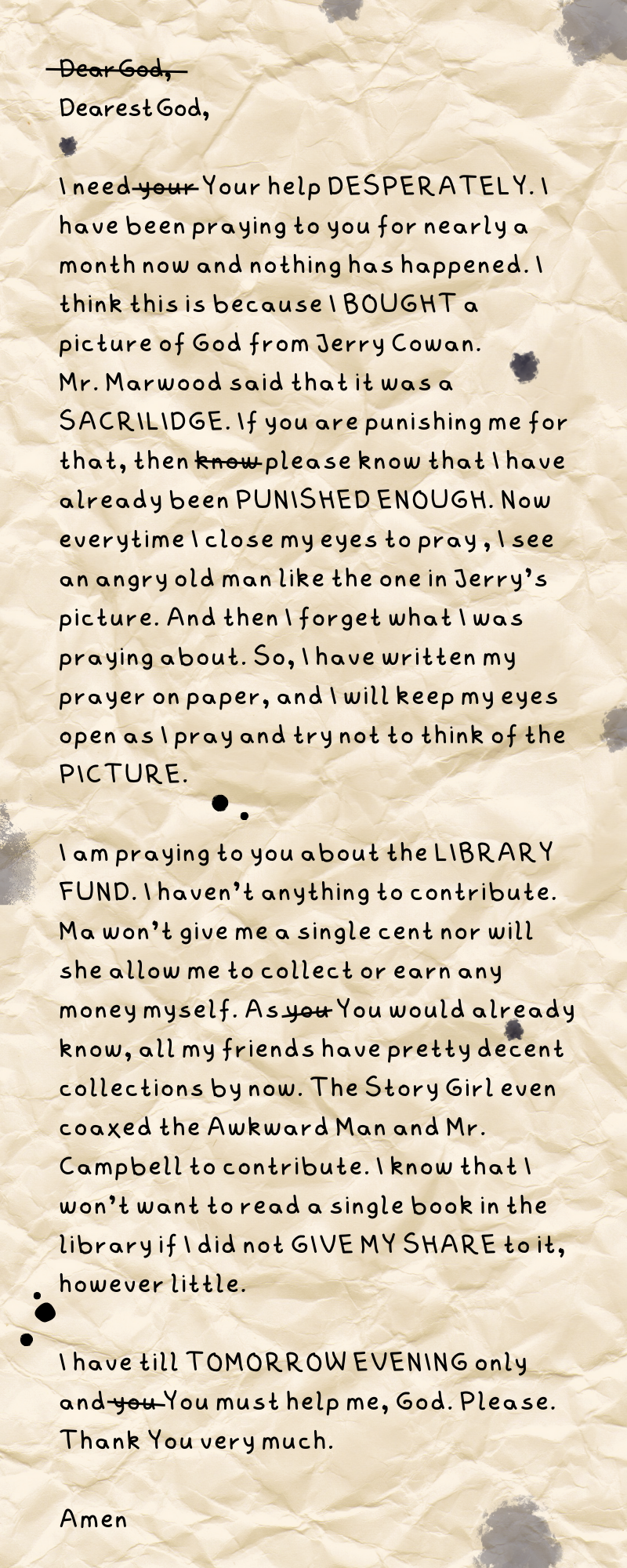

She flattened a crumpled sheet of paper on her lap. She would glance at it and then look into the setting sun, mumbling attentively. I peered at what looked like a letterTEXT while she completed her ritual.

By the time she finished her improvised prayer, the sheet was soggy with tears. Forgetful of the paper, she folded her dejected hands in worship. Her eyes were clenched, and her wet cheeks glistened dimly in the summer twilight.

A heavy dew enveloped the orchard, and I felt the dampness acutely on the Pulpit Stone. Yet, I did not stir. I could not stir, actually. Trees, grass, bushes … sky, wind, dew … contrived a holy stillness. Sara, no longer weeping, was hushed in the orchard’s embrace. Only aspen poplar leaves trembled in that sacred moment.

The faint aroma of the White Ladies in Uncle Stephen’s Walk crept on us and suffused us with the glamour of the orchard. “They look like the souls of good women who have had to suffer much and have been very patient,” the Story Girl had explained when she had named these dainty flowers. They had no name otherwise because they did not grow anywhere else, did not appear in any floral catalogue, and so were quite unknown to the world. But to our little universe, their demure charm made all the difference.

With hands clasped, Sara Ray emerged from her devotional mood. We lingered.

“Thank you for staying with me, Paddy. I didn’t quite expect you would.”

As she rose and dusted her dress, I jumped off the Pulpit Stone, stretching in readiness for a long walk and perhaps another hearty meal. We advanced toward the hill.

“Oh, you don’t have to follow me, Paddy. I don’t need an escort, even though it is rather dark for me. I’m feeling much better now. Hopeful and … serene … like this orchard. Don’t you feel so too, Paddy? Anyway, ma will have sent Judy in search of me. I’ll meet her halfway. And if I don’t, then do you see that star yonder? It’ll guide me and take care of me. You better run off to the Story Girl.”

Her tear-stained face gazed up confidently, where an evening star was shining through the last vestiges of primrose sky. The brilliance of that star was enhanced by the dark silhouette of pine trees. As Sara Ray trekked homeward, the star twinkled knowingly. Its living whiteness hastened to light her way.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful for the feedback and support I have received during the process of editing this story. Thank you to editor Lesley Clement, who has improved each draft with several insightful comments and edits. Thank you also to copy editor Jane Ledwell and the anonymous editorial reviewer for their valuable suggestions and guidance. I appreciate the patience and care that coordinator Katherine Stratton and editorial assistant Barbara Rousseau have extended in the final stages of publication. Finally, thank you to my dear friend Kritika Vaid for letting me know that the “illustration” is not half bad.

About the Author: Sameera Chawla is a writer and independent scholar based in India. She holds an M.A. in English from the University of Delhi and is about to join the University of Cambridge for an MPhil in Education (Critical Approaches to Children’s Literature). Her research interests cluster around animals in children’s stories and the children’s fiction of L.M. Montgomery. Sameera was a child herself when she discovered a yellowed copy of Anne of Green Gables on her grandmother’s bookshelf. It was a book that no one remembered buying, borrowing, or even noticing until that day. Even though the book appeared rather mysteriously, its influence has not been as unexplainable. It sparked an abiding interest in Montgomery's writings, which remain an inexhaustible source of friendship and inspiration. You can find Sameera on Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

Banner Image: Book cover of The Story Girl, 1911. McGraw-Hill Ryerson, ca. 1975. Cover illustration by Patricia Stewart. kindredspaces.ca, 111 SG-MHR.

- TEXT Dear God [crossed-out], Dearest God, I need your [crossed out] Your [initial capital] help DESPERATELY [all capitals]. I have been PRAYING [all capitals] to you for nearly a month now and nothing has happened. I think this is because I BOUGHT [all capitals] a picture of God from Jerry Cowan. Mr. Marwood said that it was a SACRILEGE [all capitals]. If you are punishing me for that, then know [crossed out] please know that I have already been PUNISHED ENOUGH [two words in capitals]. Now every time I close my eyes to pray, I see the sight of an angry, old man just like the one in Jerry's picture. And then I forget what I was praying about. So I have written my prayer on paper and I will keep my eyes open as I pray and try not to think of the PICTURE [all capitals]. I am praying to you about the LIBRARY FUND [two words in capitals]. I haven't anything to contribute. Ma won't give me a single cent nor did she allow me to collect it or earn it myself. As you [crossed out] You [initial capital] would already know, all my friends have pretty decent collections by now. The Story Girl even coaxed the Awkward Man and Mr. Campbell to contribute. I know that I won't want to read a single book in the library if I did not GIVE MY SHARE [three words in capitals] to it, howsoever little. I have till TOMORROW EVENING [two words in capitals] only and you [crossed out] You [initial capital] must help me, God. Please. Thank You very much. Amen.

Article Info

Copyright: Sameera Chawla, 2022. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.

Copyright: Sameera Chawla, 2022. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.